Last

year I took the opportunity to look over the papers of one James W. Lynd. You probably don't recognize the name—he's

not among the more famous people in American frontier history, though perhaps

he should be as he casts a very long shadow.

Born in Baltimore in 1830, James Lynd moved to Minnesota in 1853 in

order to study the language, culture, and history of the Dakota Indians. His intention had been to write a book about

their history: a project he was never able to bring to fruition. Somehow along the way he also served a term

as a Minnesota state senator (everyone was a senator in those days it seems),

but this isn't why he didn't finish his book, nor why he casts a long

shadow. Because James William Lynd was

also the very first person killed in the Dakota Uprising of 1862.

.png) |

| James W. Lynd |

On

the morning of 18 August 1862, the dawn of the infamous massacre, it so happened that

Lynd was at the Nathan Myrick & Company trading post of the Lower Agency at

Redwood, Minnesota. In one moment, Lynd

was standing at the doorway to the post, sipping from his morning cup of

coffee, and in the next a Dakota man named Thawásuota ("Plenty Hail")

was coming towards him and announcing: "Now I will kill the dog who would

not give me credit!" Thawásuota

then shot Lynd dead through the torso.

Thus began the massacre: what one historian calls "the most violent

ethnic conflict in American history."

The

irony for Lynd is that in all likelihood Thawásuota wasn't even planning to

kill him. His intended target—the "dog"

who had denied him his credit—was the notorious Andrew Myrick, brother of

Nathan Myrick who ran the store. Andrew

has gone down in history as having indirectly provoked the massacre by once

declaring that if the Indians are hungry then they can "eat grass"—but

it's actually doubtful he ever said such a thing, as is the story of his dead

body being found with its mouth stuffed with grass. Nevertheless, Myrick was known to have been

"peculiarly obnoxious" in the words of a contemporary. He was killed shortly after Lynd.

If

Thawásuota or one of the other Dakota had recognized James Lynd, it's perhaps

possible that they might have spared his life.

Lynd had married two Dakota women à

la façon du pays and had sired by them three children. He spoke the Dakota language fluently, and

they in turn had given him the name Wičháwanap'iŋ or "Raccoon

Collar". Many such white

Minnesotans were saved from the massacre by their Dakota friends and

in-laws. But then again, many weren't .

. . after all, Myrick too had a Dakota wife.

.png) |

| Thawásuota |

Over

600 settlers would die in the ensuing massacre.

In response to this bloodfeast, a punitive military expedition was

dispatched into Dakota Territory, whilst back in Minnesota thirty-eight Indians

were hanged on the gallows in the largest single day execution in United States

history. But more than that, one could

argue that the uprising cast a net of resentment and paranoia over the whole frontier

and stoked yet more calamities—chief of which was the Sand Creek Massacre,

which in turn led to a half-dozen further Indian wars flaring up before

decade's end. Could it all have been

avoided without the killings in Minnesota?

Who knows.

The

manuscript for Lynd's book only narrowly escaped from all this. The papers were being kept at Nathan Myrick's

post, and after killing Lynd the Dakotas tossed the trunk containing them into

a nearby ravine where they then languished for several months. The following Spring of 1863, the trunk was

recovered by a company of American soldiers, but this wasn't the end to the

indignities. The privates—who may have

been no more literate than the Indians—took to tearing away scraps and using

them as gun wadding. Much of the

manuscript was lost in this way, until the troop captain recognized its value

and ordered his men to stop. From here the

papers found their way to the Minnesota Historical Society where they remain

still. [1]

Aside

from the saga of the physical pages themselves, the Lynd manuscript is

interesting for being among the first "secondary source" type

monographs written specifically about the history of the Sioux tribe. In fact it might be the very first such word,

at least that I know of—everything older are things like fur trader and

missionary journals, government reports, or studies on Dakota religion. Despite this fact, Lynd and his work have

mostly been ignored in favor of his more prolific contemporaries like Stephen

Riggs, T. H. Williamson, or the Pond brothers—all of them missionaries, and all

of them fortunate survivors of the massacre.

One

reason for this neglect is that, actually, Lynd's book isn't all that

good. James Lynd shared your typical

suite of 19th century neuroses concerning Native American ethnography: page

after page is spent debating whether Indians descend from either the Japhetic

or Shemitic races of mankind; there is a chapter titled "Early

History" which is mostly empty speculation about whether the Sioux

preserve some ancient memory of the Bering Land Bridge migration (spoiler: they

don't); and very little is recorded of what the Sioux of Lynd's time still

remembered from more recent eras.

But

there's another reason. After surviving

the Indians, the elements, and the Army, the Lynd papers were put into the

hands of Stephen R. Riggs, noted 19th century Dakota-ologist. Riggs would go on to publish one chapter of

the Lynd manuscript which survived intact (titled "Religion") in the

journal Collections of the Minnesota

Historical Society (vol 2). Along

with this chapter, Riggs included a brief introduction and summary of the

remaining Lynd chapters, some of which weren't in a condition to be

published. Unfortunately this one

chapter was published under the title:

"History

of the Dakotas; by Hon. James W. Lynd; with introductory note by Rev. S. R.

Riggs"

This

was also published separately as a booklet, which you can find on archive.org.

Riggs

is clear in his summary that another of Lynd's chapters (titled "Dakota

Tribes of the N. West") also survived intact and in publishable condition,

as well as major portions of several others.

However, the misleading title of the one chapter he did publish has

apparently led others to assume—or misremember—that this amounts to the

entirety of the surviving Lynd materials.

It does not.

I

have been told that the full Lynd papers were all published

"somewhere" by the Minnesota Historical Society . . . but after

looking over their entire catalog on the Internet Archive I have found nothing,

except for the aforementioned chapter edited by Riggs, and one short passage

quoted by Albert Goodrich (in the 1915 issue).

If the rest of the manuscript was ever published, anywhere, then I have

no idea where. But I think it's telling

that on the times I have seen a scholar cite James Lynd's writings, their citation

has always been to the Riggs-edited chapter and never anything else (except

Goodrich again, who quotes the manuscript).

From all this I can only conclude that people generally aren't aware

that the unpublished portions even exist.

So

what does the manuscript say? Well as I

said, not a whole lot really. Lynd's

book may be the first of its kind, but I doubt he ever got to know the Dakotas

personally as well as the missionaries did.

But the reason I'm talking about it is because Lynd is the only writer

to ever refer to a particular "lost tribe" whom he calls the

Unktoka. He mentions them in two places:

"The Unktoka occupied the country south of

the Saint Croix river, east of the Mississippi.

The meaning of the word is "Our enemies". They were totally destroyed by the Iowas and Isanyati Sioux, before the commencement of the present

century."

(James

Lynd, manuscript, chapter titled "Dakota Tribes of the N. West")

"From

the time that the Sioux first occupied the head waters of Lake Superior to the

year 1640, it is impossible to say much of the Dakota tribes. The Sioux gradually moved south and west,

pressing upon the Iowas, Winnebagoes, and a tribe of Indians called Unktoka of Dakota extraction, which last

named tribe was afterward annihilated by the joint warfare of Sioux and

Iowas. This migratory movement must have

been very gradual, however; for the distance from Mille Lac to lake Superior is

but fifty miles in a straight line—a very moderate days journey for a Dakota

under pressing circumstances. It is

probable that the Sioux, for many years after their removal to Mille Lac, were

in the habit of hunting in the lands immediately west of lake Superior; for

they were seen there in numbers by Father Alloüez in 1665 at the mouth of St.

Louis river, and subsequently by the French traders."

(James

Lynd, manuscript, chapter titled "Migration and Treaties") [2]

Riggs mentions the Unktoka briefly in his summary of the Lynd papers, and later again in his Dakota Grammar (1893), but his information is limited to what he found from the Lynd papers; he was never told anything else about them from the Dakotas. Aside from that, nobody else seems to know anything more about these "Unktoka". I know of no other writer—no historian, linguist, or frontiersman—who has so much as uttered the name. Nor is there anything online. It's a near total hapax legomenon, of which there are actually quite a few in frontier history . . . but I figure I might as well write about this one. But what can we make of this: who were the Unktoka, and were they really a "lost tribe" as James Lynd said?

* *

*

Lynd

tells us four basic facts about the Unktoka:

- They were Siouan.

- Their name means "Our

Enemies" in Dakota.

- They were located south of the St

Croix river.

- They were destroyed shortly before

the year 1800.

At

leaset three of these claims can be seriously questioned.

FIRSTLY,

that they were Siouan — Lynd lists the Unktokas as one of 19 Siouan-speaking

tribes (or "Dakota" in his nomenclature). The other 18 are listed as:

Sioux, or Dakota

Assinaboines

Mandans

Apsarokas or Crows

Winnebagoes

Osages or Washashas

Kansas

Kappaws [Quapaw]

Ottoes

Missourias

Iowas

Omahas

Poncas

Arickarees [Arikara]

Minnetarees or Gros-Ventres [Hidatsa]

Arkansas [Quapaw]

Pawnees

Ahahaways [Hidatsa]

If

Lynd is correct that the Unktoka were a Siouan-speaking tribe and were distinct

from the others on this list, then they must have been a tribe unknown to

modern science, because there isn't any other Siouan tribe "missing"

from this list (except for the Ohio Valley Siouans whom you wouldn't expect

anyway, and the Stoney who would be included under Assiniboine). As you may have noticed, however, we can't

just take Lynd at his word here. His

list is overstuffed. The Quapaw are

listed twice as both the "Kappaws" and the "Arkansas", and

the Pawnee and Arikara are erroneously listed as if they are Siouan tribes

(they are in fact Caddoan). Lynd does

seem to be aware that the name "Gros Ventres" can refer to two

different tribes, however he still mistakenly believes that both of them are

Siouan—in reality only one is (the Hidatsa, or "Gros Ventres of the

Missouri"), while the other (the Atsina, Aaniiih, or "Gros Ventres of

the Prairies") are Algonquians.

Only the latter is still called Gros Ventre nowadays.

"Minnetarees

or Gros-Ventres : This nation includes both the Minnetarees or Gros Ventres

proper and the Gros Ventres of the

Prairie. The former number about

900, and occupy the country adjoining the Mandans; the latter are wanderers

between the head waters of the Missouri and Saskatchewan rivers, and number

about 2000."

(James Lynd, manuscript, chapter titled

"Dakota Tribes of the N. West")

A

tribe called the "Ahahaways" are listed, whom Lynd refers to as

another "lost tribe" like the Unktoka. In reality these people were also Hidatsas .

. . kinda . . . actually they were one of the three originally independent

villages who later formed the tribe now known as the Hidatsa. [3] Based on the information that Lynd provides,

his source for the Ahahaway must have been Henry Schoolcraft, and Schoolcraft's

source was the explorer William Clark.

Clark lists the Ahahaway in his 1804 Fort

Mandan Miscellany as if they were an entirely separate tribe, which at the

time they essentially were. But all of

this shows that James Lynd was working from multiple printed sources for his

book—some of which he didn't entirely understand. In other words, not everything he writes was

necessarily an unfiltered record of Dakota oral tradition as told to him

directly.

SECONDLY,

that the name Unktoka (Uŋkthóka)

means literally "Our Enemies" in Dakota — The construction of this

word seems a little strange to me. In

fact I'm not sure if it's grammatically correct, though I can't say for

sure. Nouns that are marked for

possession like this usually have a tha-

element prefixed (as in the name of Crazy Horse: Tȟa-šúŋke Witkó, "His-Horse-Is-Crazy"). There is a class of nouns referring to family

members and body parts which can be marked for possession without the tha-, but I can find no indication in

any of my Lakota and Dakota references that thóka

"enemy" is such a word.

Furthermore, even if you were to allow that, then phonologically the

full uŋk- prefix isn't typically used

before a consonant-initial stem. In such

cases it's shorted to uŋ- or

sometimes lengthened to uŋkí-.

But

I don't really know a lot about Dakhóta grammar. For what it's worth, Stephen Riggs seemed

unconcerned by the name, and he is supposed to have spoken excellent Dakota: his

grammar and dictionary are still the standard references for the Mdewakanton

dialect. So maybe this is fine...?

A

name meaning literally "Our Enemies" may sound a bit vague to be the

name of just one, particular group of enemies, but this is actually not a

problem. In Assiniboine, the sister

language of D/Lakota, the same root tóga

is used to mean both "enemy" in general and "Gros Ventre"

specifically. In the Stoney language (the

redheaded stepchild of the Dakotan family, and I mean that with love) the Blood

tribe of Blackfeet are called the Togabi.

[4]

And

THIRDLY, that the Unktoka were destroyed shortly before the beginning of the

19th century, or a bit more than half a century prior to when Lynd was writing —

It's a little unbelievable that an entire Native American group would have

existed in Iowa/Minnesota this recently without anyone noticing. If you push the date back to the 17th or even

the early 18th century then the idea is more plausible—Lynd after all wasn't

explicit on how long before 1800 it

was. There's a comparable situation for

the Assiniboine. There is a persistent

tradition which states that the Assiniboine split away from the Sioux at some

point in the past. Usually it's supposed

to have been the Yanktonai band from whom they broke off: this particular

detail isn't supported by the linguistics, but the two tribes are nonetheless

related.

As

for when they schism happened, that's another matter. The historian Arthur J. Ray in Indians in the Fur Trade makes the point

that for the entire duration of the 1700s, writers kept on saying that the

Assiniboine departure was just "fifty years ago". In other words, for a whole century no one ever

bothered updating the tally—and I'm sure I once found an example Ray missed

from the 1800s, too. And in fact they

were wrong even in 1700: a tribe called the "Assinipour" was first

noted by the French in 1640. So whenever

the Sioux-Assiniboine split happened (linguists estimate a millennium ago, give

or take), it was much earlier than when people were saying, so maybe the same

is true for the destruction of the Unktoka.

* *

*

Suffice

is to say then that James Lynd was a little sloppy with the information he gave

about the Unktoka. We probably can't

trust all of it; maybe we can't trust any of it. A person might still wonder, though, who were

they . . . were they even anybody at all?

Well they might not have been.

But if we assume for the sake of argument that most of what James Lynd told us about them is vaguely correct, then there are a few possibilities. I can think of three.

The first hypothesis would be a group of Hurons (or maybe Petuns) and Odawas who

refuged on Isle Pelée for a few years during the 1650s. Isle Pelée or "Bald Island" (so

called because it was bare of trees), also known as Prairie Island, is a large

eyot in the midst of the Mississippi River about ten miles downstream from the

St Croix embouchure. These people were

part of the great disapora of tribes from east of Lake Michigan, who were

seeking refuge in the west away from the ravagings of the Iroquois and Neutral

confederacies. The incident was

described by Nicholas Perrot:

"The

Outaoüas finally decided to select the island called Pelée as the place of their

settlement; and they spent several years there in peace, often receiving visits

from the Scioux. But on one occasion it

happened that a hunting-party of Hurons encountered and slew some Scioux. The Scioux, missing their people, did not

know what had become of them; but after a few days they found their corpses,

from which the heads had been severed.

Hastily returning to their village, to carry this sad news, they met on

the way some Hurons, whom they made prisoners; but when they reached home the

chiefs liberated the captives and sent them back to their own people. The Hurons, so rash as to imagine that the

Scioux were incapable of resisting them without iron weapons and firearms,

conspired with the Outaoüas to undertake a war against them, purposing to drive

the Scioux from their own country in order that they themselves might thus

secure a greater territory in which to seek their living. The Outaoüas and Hurons accordingly united

their forces and marched against the Scioux.

They believed that as soon as they appeared the latter would flee, but

they were greatly deceived, for the Scioux sustained their attack, and even

repulsed them; and, if they had not retreated, they would have been utterly

routed by the great number of men who came from other villages to the aid of

their allies. The Outaoüas were pursued

even to their settlement, where they were obliged to erect a wretched fort;

this, however, was sufficient to compel the Scioux to retire, as they did not

dare to attack it."

- Nicholas Perrot

(in: Emma Helen Blair, The Indian Tribes of the Upper Mississippi, pp 163-4)

The

occupation of Isle Pelée lasted from 1657~8 to 1660, after which the Hurons and

Odawas turned back east toward Chequamegon Bay.

Aside from a couple inconsequential details, Nicholas Perrot is our only

source for this episode—it makes you wonder how many other such episodes we

don't know about. Some of the details

match what Lynd says: the location of Isle Pelée is more or less "south of

the Saint Croix river" where the Unktoka were supposed to have lived, and

they were driven out by the Sioux.

Perrot tells us nothing about the Ioway being involved, however, nor do

the Odawa (Algonquian) or the Huron-Petun (Iroquoian) speak a Siouan

language. And even though the Odawa and

the Chippew are two somewhat distinct groups, I'm still not sure if the Dakotas

would have forgotten that there were Ojibwes involved in this incident, given

how important Dakota-Ojibwe warfare was to their history. [5]

* *

*

The

second hypothesis is a bit more complicated, and quite a lot more speculative. It allows the Unktoka to have been a

Siouan-speaking tribe, though it still doesn't follow all Lynd's critera

exactly (probably nothing does). This

idea involves the Ioway.

According

to the typical interpretation of history, when Europeans first began probing

this area in the late 17th century they found the Ioways inhabiting two

blocs. The first bloc was along the Root

and Upper Iowa rivers in northeastern Iowa/southeastern Minnesota—these were

the first Ioways identified in the written history. A second bloc of Ioway lived further west, in

the "Great Lakes" region of Iowa accessible via the Des Moines River

from the east or via the Little Sioux from the west. These Ioways were neighbors of their sister

tribe the Oto, and they likely also controlled the famous Pipestone Quarry in

southwestern Minnesota. At some point

prior to 1697 (probably around 1685) the Ioway abandoned the eastern bloc under

pressure from Algonquian tribes (the Ioway were still on good terms with the

Sioux at this time) and they concentrated at the western bloc. In time, the northern Iowa prairies would all

be taken over by the Sioux. [6]

A

few years ago there was an interesting article published in the Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology,

written by Colin M. Betts: "Paouté and Aiaouez: A New Perspective on Late

Seventeenth-Century Chiwere-Siouan Identity (2018). In this article the author makes the argument

that until the 1680s, these two Ioway blocs were actually in a sense two

separate Ioway tribes.

The

English name for the Ioway tribe—and for the state of Iowa, which used to be

pronounced "Ioway" (I'm told my grandfather said it like this)—is

ultimately derived from the Sioux word Ayúȟwa. This was borrowed into the languages of the

Algonquian tribes living east of the Ioway and the Sioux, from whom it was then

borrowed by the French who spelled it like "Aiaouez". The French version of the name was probably

said with 4 syllables "A-ia-ou-ez", reflecting the syllabification in

the Algonquian versions: Miami-Illinois Aayohoowia,

Fox A:yohowe:we, Menominee Ayo:ho:wɛ:w, Shawnee Ha:yawʔhowe. But the name for the Ioway in their own

language is entirely different: Báxoje

in the practical orthography, or Páxoče

in Americanist notation. This name was

also adopted by the French who referred to the Ioways as the

"Paouté". [7]

Betts

bases his argument upon a close tabulation of the earliest French references to

the Ioways: specifically which of the

two names are used when to refer to

people living where.

He

also points out that technically, both Aiaouez and Paouté are exonyms:

according to James Owen Dorsey, the Ioways' original name for themselves was Chékiwére. I believe the significance of this is

misplaced. Betts uses this to disprove

the idea that Aiaouez and Paouté constitute an exonym-endonym pair for the same

tribe, but the names both being exonyms doesn't necessarily mean that they

refer to two different groups. He also

cites Mildred Mott Wedel in support of the idea that Báxoje was originally the Otoes' name for the Ioway—and not a name

the Ioway used for themselves—but I don't think this is what Wedel says at

all. The question of how and why the

Ioways abandoned the self-designation Chékiwére

in favor of Báxoje remains, in my

opinion, unresolved. Dorsey's

explanation—that they used different names depending on whether they were on

home turf—just doesn't seem plausible to me.

In any case, there's a parallel situation with the Oto, who call

themselves Jiwere but evidently used

to call themselves Watótta. [8]

Putting

the Oto aside, it would at least make sense why the Ioways have had two

different names for themselves (Baxoje and Chekiwere) if in fact they descend

from two different founder populations.

According to this view, the Báxoje

were the "Paouté" of the upper Des Moines river, and the Chékiwére were the "Aiaouez"

of the Root and Upper Iowa. After 1685,

when the two tribes moved in together, they were thenceforth referred to using

either one or the other of their original two names. And if the one of them (probably the

Chekiwere) were James Lynd's Unktokas, then they wouldn't quite be a "lost

tribe" in the sense of an extinct one—their descendants are counted among

the modern Ioway—but their original separate identity was lost and forgotten.

Colin

Betts to be clear doesn't quite say that the Paouté and Aiaouez were two

separate "tribes". He prefers

terms like "locality" and is apparently of the view that both

localities hosued people belonging to the same overall Ioway nation. This might be the case: the evidence isn't

exactly conclusive either way—the Aiaouez may even have been closer to the

Winnebago for all we know (though I doubt it).

But part of this is just semantics: what exactly one wishes to use the

word "tribe" to refer to. You'd

have to use a time machine to learn to what extent the Aiaouez actually thought

of themselves as distinct from the Paouté.

But

it's not implausible that there were once more tribes in "Greater

Wisconsin" than we currently know about.

This part of the country endured quite a few changes in the 16-17th

centuries—most of the tribes famous to this area were relative newcomers; only

the Sioux, Winnebago, Menominee, and Chiwere are what you might call the aboriginal

inhabitants. The Fox, Sauk, Kickapoo,

Mascouten, and Potawatomi came as refugees in the 1600s fleeing from Iroquois

and Neutral raids. Huronians like the

Wendat and Petun came as well and, as aforementioned, some of them briefly

settled along the Mississippi. The

previous century-and-a-half or so had already seen the Wisconsin Ojibwe migrate

westward from the Great Lakes nexus at Mackinac, and the Omahas come up from

their ancient home on the Ohio River.

Groups of Miami and Illiniwek also arrived from the east, coming either

in the 16th or 17th centuries.

|

| [9] |

Having

a dozen tribes move in over the course of a handful of generations can only

have been a massive disruption to the human geography of this area, and the

status quo ante is very difficult to work out . . . probably impossible in its

details. But there is evidence of at

least one "lost" Siouan language spoken not far from this area—where exactly

is hard to say—which came within a gnat's toe of being lost completely and

forever without anyone ever noticing it existed. I am referring to Michigamea.

The

Michigamea tribe were one of the subtribes of the Illinois or Illiniwek

confederacy, along with the Peoria, Cahokia, Kaskaskia, and others. The Illiniwek shared a language with the

Miami which belongs to the Algonquian family, and so naturally it had always

been assumed that the Michigamea were Algonquians as well. Then in the 1990s, the linguist John Koontz

examined the brief and hitherto-inscrutable fragments of Michigamea that were

recorded by Jean Bernard Bossu in the 1750s, and he concluded that the language

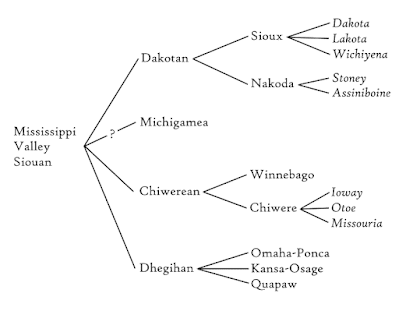

was actually Siouan. More precisely: it

belonged to the Mississippi Valley Siouan subfamily (MVS) which also includes

Chiwere-Winnebago, Dhegiha, and Dakotan.

I'm

not suggesting that the "Aiaouez" or the Unktoka were the Michigamea—that seems unlikely. But this does show that there were once more

Siouans out there than the written histories had always said. What's more interesting is that, according to

statements Koontz made on the now-defunct Siouan Mailing List, not only can

Michigamea not be any of the known MVS languages, but it might not even belong

to the three known MVS families . . .

in other words, it was neither Dakotan nor Chiwerean nor Dhegihan. A completely independent Siouan language (and

tribe) that no one ever knew about: if it's true for the Michigamea, maybe it

was true for the Unktoka and/or the "Aiaouez" as well?

Unfortunately

we can't quite hang all our coats on

this rack. Koontz himself didn't seem

fully convinced that Jean Bernard Bossus' data was reliable. On the Mailing List he raised the possibility

that Bossu just misrecollected various bits from other Siouan languages which

he could imperfectly spoke, and created from them a frankenstein's monster of

Mississippi Valley Siouan—hence Michigamea's eclectic mixture of features. It's also the opinion of some that, actually,

the Michigamea were an Algonquian group who turned Siouan, rather than the

other way around. I personally disprefer

that hypothesis, but even if true then they must have picked the language up

from somebody. [10]

* *

*

The

Aiaouez/Chekiwere explanation is probably my favorite Unktoka hypothesis, even

if it might not be the most likely. Besides,

though: the Colin Betts article with its Two Ioways thesis is extremely

interesting regardless, even if it ends up having no such Unktoka connection. The third hypothesis is similar to the first,

and it also sacrifices the Unktokas' putative Siouan status, but has more other

points in common with Lynd's testimony. I

recently read Mark Walczynski's book Jolliet

and Marquette, about the 1673 French exploration of the Mississippi River. In it he has this footnote:

"Recently,

[David] Costa discovered that the Kaw referred to the Ottawa as

"Indokah". [Michael] MCafferty

speculates that "Indokah" ~ *inohka might have been a word used by

Siouan speakers south of the Great Lakes to refer to the Great Lakes

Algonquians in general. Miami-Illinois

had extensive prehistoric contact with Siouan speakers[...]"

(endnote 5:22)

The

word inohka here (technically ī̆nō̆hka) is the name which the

Illiniwek used to refer to themselves. I

can't find anything more about this "Indokah" name that the Kansa

used for the Odawa, but in another publication David Costa mentions a name

"Intuka" which the Quapaw used to refer to the Peoria Illiniwek. McCafferty thinks this name is related to Inohka and perhaps it is. But it's hard not to notice that these

Dhegiha words also bear some resemblance to "Unktoka".

Would

that require the "Our Enemies" translation to be abandoned? It might . . . though I'm not sure. I would note that thóka meaning "enemy" has no cognates outside of Dakotan;

I would also note that there is no known, recorded word in Dakota that refers

to the Illiniwek, though they must have had one as the two tribes were deadly

adversaries in the 1600s. But by the

mid-1800s the Illiniwek had long ceased being major players. The Sioux at that point might not have

remembered much about them anymore, and the word they once used to refer to

them—or for "the Great Lakes Algonquians in general"—could have

gotten whittled down to something else, a word for any enemy. [11]

If

instead of Illiniwek they were actually Miamis, then there might be a

historical record of the incident Lynd describes. In the unpublished "Memoires" of

Pierre-Charles Le Sueur, written about 1700-ish, there is a comment that

"the Miamis lived formerly inland to the east of the Mississippi[;] five

or six years ago the Sioux and the Ayaouez practically destroyed them and

finally compelled them to abandon their country and withdraw much farther

toward Canada" (quote by

Wedel). This is quite similar to what

James Lynd says about the Unktoka: that they were "east of the

Mississippi" and were destroyed by "the Iowas and Isanyati

Sioux". From an objective standpoint,

this hypothesis fulfills Lynd's criteria the best . . . but like I said, the

Aiaouez idea is still my favorite.

NOTES

[1] – My sources for James Lynd's

life and death are Dakota Dawn by

Gregory Michno (2011), Massacre in

Minnesota by Gary Clayton Anderson (2019), Sketches Historical and Descriptive of the Monuments and Tablets

erected by the Minnesota Valley Historical Society (1902, no author given),

and "Memoir of Hon. Jas. W. Lynd" by Rev. S. R. Riggs (Coll. Minn. Hist. Soc., Vol 3, 1880), as

well as the introduction by S. R. Riggs in "History of the Dakotas: James

W. Lynd's Manuscripts" (Coll. Minn.

Hist. Soc., Vol 2, 1889, originally published 1865). Riggs is also the one who called Myrick

"peculiarly obnoxious". The photograph of Lynd is from Monuments and Tablets; the photograph of Thawásuota is from N. H. Winchell, The Aborigines of Minnesota (Minnesota Historical Society, 1911); the photograph of Lynd's gravesite is from FindAGrave.

Michno's book discusses the

mythology surrounding Andrew Myrick's death.

Anderson's goes along with the popular, maybe-apocryphal version. Michno also suggests that Thawásuota maybe

did in fact recognize and intend to murder Lynd, and that it was Lynd who had

made the "eat grass" comment.

I find this unlikely.

I don't know exactly what Lynd

was doing at Myrick's store, aside from drinking coffee. Monuments

and Tablets says that he was "serving temporarily as a clerk", Dakota Dawn says he was "in

charge" there, but S. R. Riggs ("Memoir") merely says that he

was "then stopping" there. The

modern books both name Lynd's killer as "Much Hail" and "Tawasuota",

but Monuments and Tablets give his

name as "Waukon Wasechon Heiyadin" or "One Who Travels Like a

Sacred White Man" (i.e. like a preacher).

I don't know if this is a different man or just another name for the

same person . . . the book has a photo of Mr. WWH, and I think it looks like the same guy, but I'm not great with

faces. The exact forensic details of

Lynd's murder also aren't agreed upon.

Riggs ("Memoir") says he was shot in the back by "two

Indians, with double-barrelled guns" but most sources only name one

killer, and two at the same time sounds a little Agatha Christie to me.

Riggs gives Lynd's Dakota name as

"Raccoon Collar" or "We-cha-ha-na-pin". Wičháwanap'iŋ

is my interpretation of that spelling (wičhá

"raccoon" + wanáp'iŋ

"necklace, pendant breastplate"), but don't quote me on it. It's interesting that he writes the name in

shitty-English-approximation and not the precise phonetic orthography he uses

in his linguistic works.

The specific abuses inflicted

upon the manuscript by the American soldiers is another matter with no agreement. Reverend Riggs in "Memoir" says

they were used as "gun-wadding", but in his introduction to the

published "Religion" chapter he quotes their commanding officer Capt.

L. W. Shepherd as saying they were used for "cleaning arms", and in

the preface to the Lynd manuscripts themselves (written by J. Fletcher

Williams) it's said that the soldiers "used some of the leaves for waste

paper, and the rest were kicked about the floor of the apartment, trampled on

and stained with tobacco juice". So

yes, unfortunately they might have been wiping their asses with it.

[2] – The state of the manuscript

is such that I can only give chapter titles, not numbers. At some point the chapter "Dakota Tribes

of the N. West" was removed by Stephen Riggs so he could make a handwritten

copy. Riggs apparently never returned

this chapter to the Lynd collection.

Whoever later bound the manuscript and added a title page, index, page

numbers, table of contents, and introduction (J. Fletcher Williams, I assume)

didn't include the "Dakota Tribes of the N. West" chapter, and I have

no idea where the original is—I couldn't find it with the Lynd papers, but

luckily Riggs' copy still exists. Riggs

called the missing chapter "the first chapter" in the introduction to

the published "Religion" chapter, but on his handwritten copy it is

called "Chapter II". The table

of contents by J. Fletcher Williams has different chapters for both I and II.

Also: I lied. Lynd actually mentions the Unktoka in three places: the first and second are

in the two passages quoted. The third is

on a random piece of scrap folder where the Unktoka are labeled

"extinct" and the Ahahaway are speculated to be Mandan.

[3] – Once upon a time, the

Hidatsa-speaking peoples occupied a far greater area than they did in the

classical frontier era, and their territory overspilled the western, northern,

and possibly also eastern borders of what is now North Dakota. The western segments later recrystallized as

a separate tribe—the Crow—but this reconfiguration might not have happened

until the 18th century. Prior to then,

there were at least five groups: the Awaxawi, the Awatixa, the Xiraca (or

Hidatsa-proper), and the ancestors of the Mountain Crow and the River

Crow. But to call the first three groups

"Hidatsa" may be teleological, since they may not have originally

formed a solid group vis-a-vis the two proto-Crow bands. The Awatixa and Xiraca are said to have been

more closely akin to the Crow than to the Awaxawi—more: the Awatixa and the

Mountain Crow may have originally been closer to each other than to the Xiraca

or River Crow, and likewise for the latter two.

This is why the Awaxawi were named as their own tribe by Clark: because

at the time, they were.

I find it useful to use the

spelling "Xiraca" for the one of the original three villages, and

"Hidatsa" for the modern tribe which they made a part of—they are the

same word: the x is a guttural fricative, the r is tapped like in Spanish, and

the c is a "ts" sound. I'm not

exactly clear on the histories and relationships of the proto-Hidatsa

bands. W. Raymond Wood says that the

Awaxawi spoke one dialect and the Xiraca and Awatixa spoke another, but

according to oral tradition it was both the Awaxawi and Xiraca who once lived

in eastern North Dakota (near the Red River) before they moved west and joined

the Awatixas on the Missouri. In other

words it's not clear which of the other two bands the Xiraca were most similar

to. It would help if we knew more about

the dialects spoken by these original bands—it might not necessarily be the

case that the language we call Hidatsa is even all that similar to what was

spoken by the Xiraca.

[4] – This is assuming that 19th

century Dakota worked the same as 20th/21st century Lakota (and that I'm

understanding the latter correctly). I'm

basing this off of the New Lakota

Dictionary and the Lakota Grammar

Handbook by Jan Ullrich and Ben Black Bear, which are the most thorough

analyses of Lakota by far. No resource

for Santee Dakota even comes close, unfortunately. Sioux words cited in this post are given in

the NLD orthography, which differs slightly from the orthography used by the

University of Minnesota. Note in

particular that Santee Dakota lacks the "rough aspirate" series of

stops (pȟ tȟ kȟ) which so characterize Lakota and Yanktonai. The Assiniboine form cited tóga is basically identical to the

Lakota tȟóka and Dakota thóka once you account for spelling

conventions, and the fact that Assiniboine's stops have generally undergone a

"softening" no doubt under influence from Plains Cree. The Stoney name, which ends in the plural

suffix –bi, is taken from the Stoney Mobile Dictionary App.

I couldn't tell you how common

generally it is in Native American languages for a word meaning

"enemy" to also mean a particular tribe, but as another example:

Clark's The Indian Sign Language

mentions that Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara signers used the same sign for both

"enemy" and "Sioux".

Regarding the questionable

grammaticality of *Uŋkthóka: it is

hypothetically conceivable that words for "friend" and

"enemy" could be considered extensionally as kinship terms for

grammatical purposes. But, again, there

is no such indication of this for either thóka

"enemy" or kholá

"friend" in any source I could find.

I also couldn't tell you why a word like Uŋkthóka, lacking the pi

suffix, appears to be possessed by a first person dual inclusive.

Stephen Riggs had this to say of

Lynd's proficiency in speaking Dakota: "I have heard a great many white

men talk Dakota, but I have yet to hear one, in all respects, talk it 'with the

fluency and idiomatic intonations of the natives' [as a writer for the Louisville Journal had claimed of Lynd]. Mr. Lynd, previous to his death, spoke the

language too well to have made such a claim for himself. But it is proper for me to say, that he did

speak the Dakota language very fluently, and doubtless understood its

grammatical construction better than most white men in the country"

("Memoir"). So Lynd could

definitely speak the language, but at the same time, Riggs here sounds a bit

like he's trying not to speak ill of the dead.

[5] – The dating of the Isle

Pelée incident is from James A. Clifton, Hurons

of the West: migration and adoptions of the Ontario Iroquoians, 1650-1704. According to him, the "Hurons" of

Perrot were actually Petun.

[6] – Mildred Mott Wedel's Peering at the Ioway Indians Through the

Mist of Time (1986) is fundamental for 17th century Ioway history, but she

is a bit more literalist in he read of the sources than I would be. According to her, there was only one locale

of Ioways at any given time during the 1600s: first they were in northeastern

Iowa, then they moved to northwestern Iowa and subsequently zigged and zagged a

bit. This differs from Betts'

reconstrution, both on the first map (from Oneota

Historical Connections, 2015, Shirley J. Schermer at al.) and the modified

one from his Aiaouez/Paouté article. The

French wrote in the 1680s that the Ioway were accessible from the Mississippi

via a certain river, which may have been the Des Moines or the Iowa River. Betts identifies it as the Des Moines, which

leads to northwestern Iowa. Wedel seems to favor the Iowa River—specifically

the Cedar River by way of the Iowa River, whose headwaters are a stone's throw

away from the upper Upper [sic] Iowa River in northeastern Iowa.

[7] – The usual etymologists cite

the Dakota form Ayúȟba as the word

which the Algonquians borrowed, but it's quite obvious that they actually

borrowed a form more like Ayúȟwa

which currently exists only in the Teton (Lakota) dialect. It seems less likely that the Algonquians

borrowed this name specifically from the plainsgazing Lakotas than it is that Ayúȟwa is closer to the original form as

once spoken by all seven divisions of the Sioux, and that this "Old

Sioux" version was what the Algonquians borrowed. The Comparative

Siouan Dictionary doesn't reconstruct any cognate sets for Lakota ȟw ~ Dakota ȟb, but the similar cluster of Lakota sw ~ Dakota sb is found

in words like "comb" and "rattle", where it goes back to

Proto-Dakotan *sw. On the other hand,

David Rood said that he did "not know whether [b] or [w] is older" in

sets of sw ~ sb. (in: Advances in the

study of Siouan languages and linguistics, ed Rudin & Gordon, 2016).

There is a feature common to most

Siouan languages which regularly alternates between final –a and –e on

verbs. I've seen this invoked to say

that the Algonquian forms were actually borrowed from something like Ayúȟwe rather than Ayúȟwa, but I'm not sure if this quite works.

The Miami-Illinois form is from

David Costa, "Miami-Illinois Tribe Names" (31st Algonquian Conf,

2000). The Fox, Shawnee, and Menominee

are from Douglas Parks' synonymy for "Iowa" in the Handbook of North

American Indians, Vol 13 (2001). Mii

Dash Geget tells me the details are a bit hard to work out for the Ojibwe name

cited by Parks, but the older Ojibwe form may have been Aaya'oowe (or, less likely: Aayo'oowe).

[8] – The Dorsey cite is: Rev. J.

Owen Dorsey, "On the Comparative Phonology of Four Siouan Languages"

(Annual Report of the Board of Regents of

the Smithsonian Institution, 1885).

Here is his explanation for the name Chekiwere:

"Ȼegiha

means, "Belonging to the people of this land," or, "Those

dwelling here," i.e., the aborigines or home people. When an Omaha was challenged in the dark, if

on his own territory, he usually replied, "I am a Ȼegiha." So might a Ponka reply, under similar

circumstances, when at home. A Kansas

would say, "I am a Ye-gá-ha," of which the Osage equivalent is,

"I am a Ȼe-ʞá-ha." These

answer to the Oto "Ʇɔi-wé-re" and the Iowa "Ʇɔé-ʞi-wé-re." "To speak the home dialect" is

called "Ȼegiha ie" by the Ponkas and Omahas, "Yegaha ie" by

the Kansas, "Ʇɔiwere itcʿe" by the Otos, and "Ʇɔeʞiwere

itcʿe" by the Iowas. When an Indian

was challenged in the dark, if away from home, he must give his tribal name,

saying, "I am an Omaha," "I am a Ponka," etc."

The Wedel cite is: Mildred Mott

Wedel, "A Synonymy of Names for the Ioway Indians" (The Iowa Archaeological Society, Vol 25,

1978). The only statement of hers I can

see which might be interpreted as saying the word "Baxoje" comes from

the Oto dialect and wasn't originally used in Ioway, is this:

"There

is another Siouan name for the Oto, watóta (Whitman 1937:xi) from which

the modern name stems. It was recorded

by Euro-Americans as being used not only by the Oto as a self-designation (e.g.

Bradbury 1811 in Thwaites, ed. 1904-07, 5:80) but also by the Ioway-Missouri

and Dhegiha speakers in early Euro-American contact situations. This has continued in the shortened form,

Oto, to the present day. It parallels,

in a sense, the possibly descriptive designations for the other Chiwerans, as paxóche

for the Ioway and ni-u-t'a-tci (Dorsey NAA 4800:307) for the

Missouri. According to Indian tradition,

the three terms all relate to the episodes of separation of these peoples from

one another after having formerly existed as a single group, all of whom spoke

a proto-"Chiwere" language.

Dorsey was told these were the self-designations used when these people

were away from home."

In fairness, the issue of which names were used by which group to refer to which other group, and how these may

have changed over time, is one which requires very careful and precise

description . . . and neither Dorsey nor Wedel were very precise or

careful. Dorsey elides over the

difference between "which language are you speaking" and "where

are you speaking it"—to be honest he sounds a bit like an alien who only

recently learned the concept of there being multiple words for things. Wedel says that paxóche "parallels" watóta

but isn't clear on how: Betts apparently thinks she's saying that they're both

words used by the Oto, but I think she's saying they are both endonyms. I'll add that if the former, then that

wouldn't very well explain why the French were using it, since they and the

Illiniwek were even further away from the Oto than they were from the

Ioway. I may be misinterpreting

something here.

"Chékiwére" is the

spelling Betts uses in place of Dorsey's "Ʇɔé-ʞi-wé-re". Since Dorsey's upside-down letters appear to

mark tenuis stops, that would be Jegiwere

in the Goodtracks orthography, or Čekiwere

in Americanist notation. I'm ignoring

Dorsey's accent marks because I don't know whether it makes sense analytically

for words in Ioway-Oto to have multiple stresses. The modern Oto self-designation is given by

Goodtracks as both Jiwére and Jíwere so I'm ignoring the accent there

as well (Wedel, using Dorsey's notes, also has the "wrong" stress for

Báxoje. Evidently Chiwere accent is difficult). Wedel's Watóta

is given by Goodtracks as Watóhda and

by Robert Rankin (in the HNAI) as watótta.

[9] –The details of these

migrations aren't my main point here, but the prior locations of the

Potawatomi, Sauk, Fox, Kickapoo, Mascouten, and Miami are discussed in various

publications by Timothy Abel and David Stothers and in the analyses of the

Huron Novvelle France map by Conrad

Heidenreich and John Steckley, among others—I'll probably dig into this in a

later post; the relative positions of the Sauk and Fox are sometimes flipped,

and the locations of the Miami and Potawatomi are particularly hard to pin

down. The ca. 1500 arrival of the

Dhegiha is mentioned by Dale Henning (in Archaeology

of the Great Plains, 1998) and is vaguely in line with Dhegiha migration

legends recorded in the 19th century. The

westward movements of the Miami and Illiniwek are mentioned by Robert Mazrim in

Protohistory at the Grand Village of the

Kaskaskia (ed. Robert F. Mazrim, 2015) and by Emerson, Emerson, &

Esaray in Palos Village: An Early

Seventeenth-Century Ancestral Ho-Chunk Occupation in the Chicago Area (ed.

Duane Esarey & Kjersti E. Emerson, 2021); these are also vague as to the

prior location of the Miami and even moreso the Illinois. The color key might be off for the

Miami-Illinois migration a bit, as I'm not sure if they came in the 16th or the

17th century. Also, not indicated on the

map, but there may have been something else going on with the Menominee and

with another tribe called the Noquet.

I tend to like using the name

"Illiniwek" rather than "Illinois" because it's easier that

way to distinguish from the state.

Despite looking "Indian-y" this is not the tribe's own

endonym, it's a respelling of their Old Odawa [Ojibwe] name. If you recognize a little Algonquian then you

might think this means "the people", but appearances are deceiving:

the Old Odawa form ilinwe:k is a

borrowing of Miami-Illinois irenwe:wa

which is a verb that means "to speak in the regular way". (In this sense it's an interesting

counterpart to the Algonquian names for Iroquoians and Siouans, which come from

*na:towe:wa "to speak in an

abnormal way".) David Costa

discusses this in his article "Illinois" for the Society for the

Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas (2007), which you can find by

googling Michael McCafferty's article "Peoria" on academia.edu. McCafferty's chapter "Illinois

Voices" in Protohistory at the Grand

Village of the Kaskaskia also discusses this, but he differs on a few minor

details.

[10] – Robert Mazrim (in chapter

10 of Protohistory at the Grand Village

of the Kaskaskia) comments that some elements of archaeological ware from

Kaskaskia have been proposed to have come from the north, around western

Michigan. No comment is made regarding

the Michigamea, but there might be a connection.

The two sentences of Michigamea

provided by Bossu are "indagé ouai panis" translated "je suis

indigne de vivre, je ne mérite plus de porter le doux nom de père", and

"tikalabé, houé ni gué" translated "nous te croyons, tu as

raison"—both obviously overtranslations.

Koontz interprets these as:

"indagé ouai panis"

įdaǰe wé bnįs

his-father neg I-am-neg

"I am not his father"

"tikalabé, houé ni

gué"

htíkdąbe wé nįge(s)

you-think neg it-lacks(-neg)

"Your thinking is not

lacking."

For some absurd reason, the

Seymour Feiler translation respells these as "Indagey wai panis" and

"Teekalabay, houay nee gai".

Maybe they were already spelled that way in John Reinhold Forster's old

1771 translation, but that's no excuse.

Walczynski's book Jolliet and Marquette (p 97) cites

Michael McCafferty as saying that "linguistic information" shows the

Michigamea to be Dhegiha. I consider

McCafferty to be trustworthy—and I don't know how much behind-closed-doors

unpublished research has been done on Michigamea since then—but John Koontz at

least was very specific in the 1990s that the language was not Dhegiha.

(Sources: John Koontz,

"Michigamea: A Siouan Language?" (from his website); John Koontz,

"Michigamea As A Siouan Language" (1995, handout for the 25th Siouan

and Caddoan Languages Conference); the Siouan Mailing List, September 2005;

Jean-Bernard Bossu, Travels in the

Interior of North America (1962) pp 73, 109.)

[11] – The Walczynski endnote is

on page 255. David Costa refers to the

Intuka in the article "Illinois"—part of the superarticle Three American Placenames—in the Society

for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas Newsletter XXV:4,

January 2007. More about Miami-Illinois

nomenclature is in Michael McCafferty's article in Protohistory at the Grand Village of the Kaskaskia. The macron-breves are because we don't know

whether the first two vowels are long or short.

The Le Sueur quotation is from Mildred Mott Wedel's article in Aspects of Upper Great Lakes Anthropology

(ed. Elden Johnson, 1974).

Both Inohka and Indokah/Intuka are unanalyzable in their respective

languages. To be honest I'm not 100%

sure that thóka has no non-Dakotan

cognates, but the Comparative Siouan

Dictionary at least has no entry for it, and the one possible cognate in

Dhegiha (as part of a compound word meaning "antelope, goat") having

a note saying it might be a Dakotan loanword.

One can imagine a scenario where

James Lynd was told a name like "Indokah" or "Intuka" and

construed it himself as "Uŋkthóka". This at least would explain why it looks so

grammatically unusual.

The uŋ(k)- prefix in L/Dakota and Assiniboine actually has a front

vowel in Stoney: į(g)- in Morley

dialect and įgi- in Alexis

dialect. And in Chiwere-Winnebago the

cognate prefix is hį-. So one might be

tempted to say that in Proto-Dakotan the word for "our enemy" could

have been *iŋ(k)thóka. That looks like something that could easily

have been borrowed to or from the Dhegiha forms, regardless of what those words

meant in Dhegiha ("our" in Dhegiha tends to have an ą or ǫ

vowel). If intuka/indokah was borrowed

into Sioux then it may have been they, rather than Lynd, who reinterpreted it

as a possessed noun (if it even is one at all).

Unfortunately, the cognates

outside of Mississippi Valley Siouan do make it look like uŋ(k)- is the older form, and it's generally good practice to

assume fewer conservatisms in Stoney anyway.

If thóka is in fact a

borrowing then it must have happened during the Proto-Dakotan period since the

word exists in Stoney and Assiniboine, and so at that time it likely wouldn't

have referred to the Illiniwek who probably weren't in contact with the Sioux

until at least the 16th century. It

might have referred to another Algonquian tribe, per McCafferty's idea that it

referred to the Great Lakes Algonquians in general? You can see that while "intuka" ~

"unktoka" looks impressionistically promising, it is very hard to

make any of the details actually work for this theory.

(Morley source: Elias

Abdollahnejad, "Verb Conjugation in Stoney Nakoda: Focus on

Argument-Marking Affixes" (2018); Alexis source: Corrie Lee Rhyasen

Erdman, Stress in Stoney (Master's

thesis, U. of Calgary, 1997))

.png)

.png)