Part 3a of a

four-and-a-half part series creating a map of the Chesapeake area and

surrounding environs circa the year 1600.

Click for: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3b, Part 4.

§

1.

Historical background

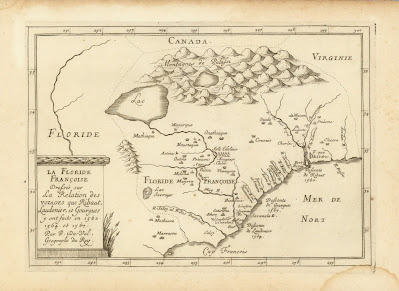

On eighteenth-century French maps

of North America you can sometimes find an interesting label under Carolina:

Carolina,

named in honor of King Charles IX, by the French who discovered and took

possession of it in 15.... / until the year 1660. This is in reference to the French Huguenot

colony of the 1560s, which consisted of Charlesfort in southern Georgia and

later Fort Caroline in northern Florida.

The French colony was destroyed by the Spanish in 1565, and while both

locations were indeed named after King Charles the Ninth of France, the idea

that he remained the namesake of English Carolina was as the kids say "cope". Because the area labeled on the maps clearly is English Carolina which, after all, is

named for King Charles II of England.

Furthermore, the French never even called that area "Carolina"

before the English started doing it (cf Salley 1926). They usually called it Florida, as on this

map of La Floride Françoise:

|

| Map of Pierre du Val, 1665. |

I bring this up because actually,

funnily enough, the Carolinas are still kind

of named after more than one King Charles.

If I could alter history but was

only allowed to make minor, cosmetic changes, I would see to it that South

Carolina is called "Carolina", Virginia is called

"Jacobia", and North Carolina is called "Virginia"—each

named for the monarch under whom English colonization began. That would be cleaner, but alas in our actual

timeline things are slightly messy.

North Carolina was originally named

"Virginia" when Sir Walter Ralegh's men tried planting the first

permanent English settlement on Roanoke

Island. This as you know didn't

take. There were actually two Roanoke

colonies: the first lasted from 1585-6 but was then evacuated by the legendary

English sea captain Sir Francis Drake. A

second group of colonists was planted there in 1587 but was gone by 1590, their

ultimate fate unknown: they are remembered in history and legend as "The

Lost Colony" [see note A at bottom].

In 1607 when the English returned

to settle the Chesapeake Bay, they were still within the general region they

considered "Virginia" so they inherited the name... though by now

"the Virgin Queen" Elizabeth was dead, and the capital of their new

Virginia was named James Town after King James (he of the Bible). For some time thereafter the present North

Carolina—which the English still considered theirs though only the occasional

lone adventurer existed to preserve their squatter's-rights—was sometimes

called "Old Virginia" or "South Virginia". One map from 1650 gives it the nickname

"Rawliana":

.jpg) |

| Map of John Farrer, 1650. |

Meanwhile, in 1629 a charter for

a new colony was granted by King Charles, intended to be located between

English Virginia and Spanish Florida.

However, nothing became of this planned colony as things quickly got too

hot at home—with the beheading of Charles, the Civil War, Oliver Cromwell, and

all that—and no one was in the mood for colonization. In 1663, after things had settled down a bit,

a new grant was issued by the restored Stuart monarch Charles II. It was essentially the same as the old grant

but with a slightly revised name: the original colony was to have been named

"Carolana", but the younger Charles—perhaps to make it more

"his"—named the new colony "Carolina". Both charters defined the colony as all land

lying from 31°N to 36°N between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans... which not

only arrogated the territories of several dozen Indian tribes but by

implication claimed Spanish New Mexico as well.

|

| Map from Walbert, "A little kingdom in Carolina". |

Thus Carolina was named after two

kings named Charles—only neither of them was French.

* *

*

The fruit of the Carolina grant

was the city of Charleston (or "Charles Town") founded in 1670 by a

group of English planters from Barbados.

This wasn't their first attempt: an earlier "Charles Town" had

been built at Cape Fear in 1664 but was abandoned in 1667. They in turn had been preceded by some

Puritans from New England who tried settling Cape Fear in 1663. But the second Charles Town became the real

nucleus and capital, and thenceforth the "history of Carolina" was

for all intents and purposes the history of South Carolina.

North Carolina didn't really

belong, and it should have gone on being called "South Virginia" as

it had before. If you look at the area

of English settlement in America as giant amoebae, then North Carolina first

appears as a pseudopod extending south from Virginia. People had been moving in there since around

1655 and settling along Chowan River and north of Albemarle Sound: the district

later known as the County of Albemarle. These settlers apparently called the region

"Roanoke" but officially they were Virginians. They were Virginians still when the 1663

charter came, as its original terms defined the border further south than it is

today. Only in 1665, when the border was

officially changed to its present latitude, did they become—on paper—Carolinians

(cf

Salley 1926, Butler 1971, McIlvenna 2009).

In short: North Carolina was

settled by the English in 1585-7 (unsuccessfully). It was later resettled (successfully) from 1655

onward. The seven decades in between (let's

call it the intercolonial period) are

mostly dark in the historical record, and reconstructing the Native American political

landscape circa 1600 A.D. requires some interpolation of the evidence.

* *

*

§ 2. Primary sources

It's not my interest here to retell

the whole saga of Sir Walter Ralegh and the Roanoke venture—if you need a

refresher then Lemmin0's video on Youtube is pretty good about it.

We obviously have no writings

from the Second or "Lost" Colony (except for "C R O A T O A

N"), but we do have some from the First Colony (1585-6). Alas they too are less extensive than we'd

hope. The colony's most interesting

members were John White and Thomas Harriot—they were the two I mentioned in

Part 1 who spent time among the Chesepioc.

White was an artist whose paintings are still our main visual reference

for Virginia-Carolina Algonquian lifestyles—he also made paintings of Timucuas

from Florida and Inuits from Greenland. Thomas

Harriot was a scientist and polymath who among other things is known for his

contributions to the sphere-packing problem in mathematics. Both of these men produced works which are

now lost, but it's Harriot's writings in particular that I miss the most as

they allegedly included a dictionary of the Secotan language [note B]. He had learned to speak this language (to

some extent at least) while he was still in England, by conversing with two

Indian captives taken during a scouting voyage in 1584.

|

| Comparison of some Algonquian languages around Chesapeake Bay. |

These two Indians returned home

in 1585 on the same flotilla that brought the first colonists. Despite the fact that they had essentially

been kidnapped, one of them—a fellow by the name of Manteo—became something of

an anglophile, even opting to visit England for a second time in 1586 [note C]. According to some he was even made a baron of

the English Empire and invested with fiefdoms in America: "Lord of Roanoke

and Dasamonquepeuc". I've heard

contradictory reports whether this is true or not—if it was it can't have much

pleased Chief Wingina, who was the actual

lord of Roanoke and Dasamonquepeuc, as well as several other places.

Thomas Harriot's papers were

destroyed in the Great Fire of London.

Many of White's sketches were tossed into the sea during the evacuation

of the first Roanoke colony in 1586.

Fire and water, blasted things.

But I shouldn't make it sound like all

of their materials were lost to history—they were not. Most valuable here for my purposes are two

maps made by John White: one of the Carolina sounds region:

...and another of the general

southeast:

(Incidentally, I only reference

the first map, so if I say "White's map" that's the one I mean.)

Not 100% sure when these maps

were made—I've seen them cited as from either 1585 or 1586. Nor do I know whether they were made while

White was still in America, but if they were then that might account for the

presence of certain additions and corrections on the later Theodor de Bry map of

1590. De Bry was the man enlisted to

convert White's drawings into engravings that could be printed in the published

account of the Roanoke colony. Unlike

White, De Bry was not an eyewitness to the colony, and his map is much less

geographically accurate: consequently it's sometimes seen as less

reliable. Others however think that De

Bry may have based it on an otherwise-unattested map of White's, or that he

made it in consultation with White or another colonist.

The protruding horn of the Outer

Banks that you see on these and other early maps wasn't a mistake—that's a real

feature that used to exist, called Cape Kenrick. It was destroyed by a hurricane in the early

18th century, leaving the Outer Banks as they are now. It's not something I can reproduce on my own

maps.

As for textual sources: the

surviving works of Harriot and White are useful to anthropologists for

reconstructing the life and culture of the Carolina Algonquians. But when it comes to the geography and

politics—what I need to make a map—they're of less use, and instead we have to

rely on the writings of two other men: ship captain Arthur Barlowe, and Ralph

Lane, commander of the first Roanoke colony.

It was Lane whose violent personality led to the First Colony's failure—in

particular, his ordering the death of chief Wingina. However, "[in] spite of the development

of unfriendly relations between the natives and colonists under Lane's

governorship, Lane's account shows him to have been an individual of

ethnological discernment," according to Maurice Mook (1944:184).

As scant as the records are from

the Roanoke era (1584-90), they're even scantier for the Albemarle era

(1655+). People at the time just didn't seem

to write much about the Indians—or about the interior in general—and therefore

neithor do modern authors. Quoth the

adventurer John Lawson:

"'Tis a

great Misfortune, that moſt of our Travellers, who go to this vaſt Continent in

America, are Perſons of the meaner

Sort, and generally of a very ſlender Education; who being hir'd by the

Merchants, to trade amongſt the Indians,

in which Voyages they often ſpend ſeveral Years, are yet at their Return,

uncapable of giving any reaſonable Account of what they met withal in thoſe

remote Parts; tho' the Country abounds with Curioſities worthy a nice

Obſervation. In this Point, I think, the

French outſtrip us."

(John

Lawson, preface to A New Voyage to

Carolina, 1709)

Lawson looms large in

this story. He came to America from England

essentially as a tourist, and from him

we get our most vivid description of the North Carolina Indians, as well as our

only surviving data on the Woccon and Pamlico languages. Later he became Surveyor-General of North

Carolina (map below), and was instrumental in the founding of Bath and New Bern. Even his death was important: his capture and

murder at the hands of the Tuscarora ended up igniting the Tuscarora War—possibly

the most significant event in colonial North Carolina history.

|

| Map of John Lawson, 1709. |

Anyway, aside from Mr.

Lawson's j'accuse I really can't say why the Albemarle settlers wrote so little

about the Natives. Noeleen McIlvenna

writes that the initial settlers were on fairly good terms with their Indian

neighbors... but also, Patrick Garrow writes that the records are "replete

with examples of the minor clashes" between Indians and whites (1975:18). It's probably dangerous to generalize in

either direction. But whether the

settlers liked the Indians or not,

they evidently were not interested in writing lengthly ethnological treatises.

On the other hand,

McIlvenna also says that the Albemarle settlers were mostly religious

dissidents, escaped servants, slaves,

and other such castoffs who'd fled beyond the ominously-named Great Dismal

Swamp to escape the all-seeing eye of colonial authority. They weren't "off-the-grid"

exactly... but they at least tried to keep a low profile. This might explain the dearth of primary

literature on the Native North Carolinians, since other such primary

descriptions were oftentimes written with the explicit purpose of advertising their respective colonies.

But besides that, there just

weren't as many Indians in North Carolina in the latter-1600s as there had been

a century before. The obvious culprit

here is Old World disease, to which our friend John Lawson adds liquor:

"The

Small-Pox and Rum have made ſuch a Deſtruction amongſt them, that, on good

grounds, I do believe, there is not the ſixth Savage living within two hundred

Miles of all our Settlements, as there were fifty Years ago. Theſe poor Creatures have ſo many Enemies to

deſtroy them, that it's a wonder one of them is left alive near us."

(Lawson

1709:224)

None of this is

surprising. Lawson further targets

"the continual Wars theſe Savages maintain, one Nation againſt

another"... and while it's highly unlikely that the Indians simply

exterminated themselves in this way, it is possible that the fracas between

English and Powhatan up in the Chesapeake triggered second-order shockwaves

which, among other things, intensified intertribal conflict in Carolina. I wouldn't discount slave raiding either, though

I haven't read anyone specifically mention it operating here at this time. The Francis Yeardley narrative (in Salley

1911) implies that by 1653 white fur traders had regularly been visiting

Roanoke Island—who knows how many such traders, and for how long, had been

buffeting that area with germs? It must

not be forgotten that history was still unfolding in the hinterland beyond the

main Euro-Indian frontier. For a rare

glimpse of such history, see note D.

Thus we have the

situation where our best information on the Indians of the North Carolina comes

not from the people who dwelt there for decades and decades after 1655, but

from those far fewer people who lived there only a year, and whose records

anyway were partially destroyed.

* *

*

§ 3.

Geography and Archaeology

As

I've said, North Carolina is more of a "South Virginia" from the

perspective of European settlement. The

same is true from the Native American perspective as well. The North Carolinian Indians tended to belong

to the same linguistic groups as those in Virginia: Algonquian, Iroquoian, and

Siouan. The South Carolinian Indians on

the other hand—the Peedee and Cusabo and such—well, no one really knows what

languages they spoke, but it probably was something different.

Recall

from part 1 that in North Carolina the tidewater line cuts through the coastal

plain splitting it in half.

Incidentally, this also very roughly marked the border between the

Iroquoians of the upper coastal plain and the Carolina Algonquians of the lower

tidewater. I can't entirely explain why

such an unobtrusive natural boundary would be so determinative—some say that

the lifestyles of the two groups focused on harvesting different manner of sea

creatures who are sensitive to such things.

Or maybe the hassle of paddling upriver even during high tide simply

vexed the

thalassocratic Algonquians more than the landlubbing Iroquoians? Of course the border doesn't actually match the tidewater line on any

map I've seen—more of a guideline I suppose.

The Algonquians and

Iroquoians are also distinguished by their different classes of archaeological ware. Iroquoian sites are classified as belonging

to the Cashie phase, and Algonquian sites to the Colington phase. Since archaeology is still voodoo sorcery to

me, I can't tell you precisely what distinguishes the wares from the two phases—however one difference is that the Algonquian

used crushed shell fragments to temper their pottery (meaning they mixed the

fragments into the clay to prevent shrinking and cracking) whereas the

Iroquoians used sand.

This, part 3a, is about

the Algonquians. Part 3b will cover the

Iroquoians.

* *

*

§ 4. Secondary sources

The Carolina Algonquians

get much less attention than either their relatives to the north (the

Powhatans) or their rivals to the west (the Tuscaroras, who you usually get if

you search "North Carolina Indians"), and what little press they do

get is often sidelined by attempts to solve the mystery of the Lost Colony. However I've found three sources in

particular to be especially useful in constructing the borders of the Carolina

Algonquians.

My first source is Maurice Mook, Algonquian ethnohistory of the Carolina Sound (1944). Despite being almost eight decades old, it is

to my knowledge still the most detailed and thorough analysis of the Indian

tribes and the locations of their villages.

It includes a map:

My second source is David Beers Quinn, The Roanoke Voyages, 1584-1590 (1955). Quinn's commentary on village names and

locations is found in Appendix I. It

also comes with a map: this scan was made for me by a library out-of-state so I

can't attest to what the paper quality is like, or whether anyone could make a

better scan.

My third source is Bernard G. Hoffman, Ancient Tribes Revisited: A Summary of

Indian Distribution and Movement in the Northeastern United States from 1534 to

1779 (1967). Hoffman's article has a

much broader focus, and therefore he may have less specific insight regarding

North Carolina in particular—but he offers some corrections to Mook, and unlike

him his map has borders:

Mook, Quinn, and Hoffman

are my three main sources, and I cite them often.

For comparison, some

other maps—which are less useful, but still worth looking at:

Map from Frank Speck, The Ethnic Position of the Southeastern

Algonkian (1924). I have a lot of

respect for Speck, as he was one of the first who I'd call "modern

scholars" studying Native American history, but I seldom find myself actually using

his stuff:

Map from Bernard G.

Hoffman, Observations on Certain Ancient

Tribes of the Northern Appalachian Province (1964). This was the original article which Revisited is the sequel to, and the map

it comes with has numerous issues:

Maps from Lewis Binford

(1964 and 1967). Binford was the

recognized authority on the Indians of the Carolina sounds but—since he wrote

more on the culture of the people,

and I was just looking for locations—I didn't use him much as a source:

Similar things can be

said of Helen Rountree, a specialist in Powhatan history and culture. Her newest book on the Carolina Algonquians

(2022) is less focused on geography, but it does have a map (I've added the labels

from the key caption):

Map from Gerald P.

Smith (1971).

Some of these maps are

from sources concerned more with either the Virginia Algonquians or the

Iroquoians. For the Carolina

Algonquians, you can see that the uncertainties and disagreements increase as

you go south.

* *

*

§ 5. The Carolina Algonquian

"chiefdoms?"

The Algonquians of North Carolina

(sensu lato) were the Chowanoc, Weapemeoc, Secotan, Moratuc, Pamlico, and Neusiok. These were the

southernmost of all the Algonquian tribes, and the southernmost representatives

of the vast Algic phylum of languages which extends north into Labrador and

westward almost to the Pacific Ocean.

Let's set the Neusiok aside for now—I'll discuss them along with the

Coree in the final section below, as the Neusiok language is unattested and may

not have actually been Algonquian.

There's also good, reasonable doubt as to the affiliation of the

Moratuc, although I personally think they were Algonquians too (cf Goddard 2005). The Chowanoc and Weapemeoc languages are also

unattested, but anyone who seriously

doubts their Algonquianity is just being silly if you ask me. Only for Secotan and Pamlico do we have

direct and incontrovertible evidence that they spoke Algonquian dialects—I'm

using "Secotan" here to refer to the linguistic data from the Roanoke

expeditions, and "Pamlico" to refer to the Algonquian language

recorded by John Lawson in the 1700s.

I'm not really equipped to say whether these were even separate and

distinct languages. Linguists usually

just refer to it all as "Carolina Algonquian".

Being as they were, the Carolina

Algonquians were similar to their neighbors and relatives the Virginia

Algonquians, and this includes being ruled by chiefs. As among the Powhatan, the Secotan leaders

were called weroance, and as

elsewhere the English tended to refer to these weroances as

"kings". So for instance, the

Chowanoc were said to be ruled by a king named Menatonon, the Weapemeoc by a

king named Okisco, etc. The king of

Secotan and of Roanoke island was a man known as Wingina (later changed to Pemisapan)—it was he whom the Roanoke

colonists dealt with directly. He would

eventually be killed and beheaded on the orders of Ralph Lane.

|

| John White painting of a weroance, believed to be Wingina. |

The Carolina Algonquians led

similar lives to those in Virginia and Maryland (in her book about them, Helen

Rountree will often supplement data from the Powhatan in cases where direct

info on the Carolinians is lacking). So

were they organized into chiefdoms and paramountcies, as the Powhatans and

Piscataways were? They may have been...

but the evidence is much weaker. Many

will say they were not. Wingina was weroance

of Roanoke and Dasamonquepeuc, so they say, but was not paramount chief of all

the Secotan; neither was Okisco of the Weapemeoc, et cetera. Rather these nations were alliances of

multiple chiefdoms, and if such a chief as Okisco had more credibility over his

fellow Weapemeoc chieftains, it wasn't because of his birth.

The problem is that we really

only have the Roanoke documents to go off of.

Because by the Albemarle era (1655+), the Carolina Algonquians had

become shadows of echoes of what they once were. The Weapemeoc had disintegrated into the

small bands of Yeopim, Poteskeet, Currituck, Pasquotank, and Perquiman (some of

whom may not have even existed, cf Mook 1944:221). The Secotan had dissolved into the

Mattamuskeet, the Hatteras, and the "Bay River Indians" (Mook 1944:223,

Garrow 1975:18). These tribelets

were all tiny in population. The

Chowanoc, Pamlico, and Neusiok survived, though similarly decreased in

number. The Moratuc evidently were gone.

It's not clear just what exactly

happened between 1586 and ca. 1700, and that makes it hard to interpolate the

data... balancing uncertainties on one end with other, different uncertainties

on the other. Thus it may be that the

Poteskeet, Pasquotank, etc. had originally been component tribes of the united

Weapemeoc, separating only when demographic conditions rendered such a large

chiefdom unsustainable. Or it may be

that there never was a single "Chiefdom of Weapemeoc", but the

Roanoke colonists merely assumed there was.

The Natives' subsequent population decline would have obscured the

matter in either case.

Roanoke colonists lacked the

vocabulary to give us a clear ethnographic picture, and "translating"

their feudal terminology into something that makes anthropological sense is

difficult. However, I hate and reject

the premise (implicit in some analyses) that the English were all just too

stupid to understand what they were seeing with their own eyes—that they

"only saw what they wanted to see" or other such wastrel. It's also worth saying that, being subjects

of Her Tudor Majesty, they did know a thing or two about the day-to-day reality

of living in a monarchy. And an

Algonquian chiefdom is a monarchy of sorts,

even if its parameters are different. If

the English said that Wingina was a king, then that clearly means... well, something anyway.

On the other hand, though they did

call them kings, the English did not refer to any of the chieftains as an

"emperor". The Powhatan

mamanatowicks, the Piscataway tayacs, the Nanticoke tallecks—even the

non-hereditary teethhas of the Tuscaroras—were all called emperors at one time

or another. Does it mean anything that

the chieftains of the Roanoke era weren't?

Did Wingina lack the power and splendor to merit such a title? Or are we just talking about the whims of

different sets of Englishmen, using imperial titles in very vague ways? The answer to the last question at least is

yes.

As Michael Oberg says,

"analogizing from what we know about the better-documented Algonquian

Powhatans is risky" (2020:584).

Oberg argues that there were no chiefdoms here, but he uses very strict

definitions of chiefdom and tribe.

The only author I found who explicitly says that the Carolina

Algonquians were entire chiefdoms and not

tribal alliances is Patrick Garrow (1975:16).

Most others seem to adopt a middling position where they might refer to

a "chiefdom of Secotan" or a "chiefdom of Chowanoc," but I

don't get the impression that they mean anything too specific or technical by

it—it's just a label. I do this as well.

The Chowanoc have the best claim

to being a true chiefdom: accounts make it out to be the largest and most

elaborate of the Carolina Algonquian nations.

Binford (1964:110) interprets the Roanoke documents as saying that the area

of Chowanoc was split into two divisions with a separate king over each: the

aforementioned Menatonon was king of one, and someone called Pooneno was king

of the other. Binford explicitly states

that the Weapemeoc and Secotan were not Virginia-style

paramountcies, but seems to accept that Menatonon and Pooneno were in fact true

chieftains and not just primi inter pares. Mook disagrees: he says that the document in

question is confused, and that Pooneno was subordinate to Menatonon. If so then this apparently makes Chowanoc fit

the definition of a paramount chiefdom as given by David G. Anderson [note E].

We will never know for sure. For the record I do think that at least some of

these groups were paramount chiefdoms, with the usual caveats applying. But since this is not firmly established, I

don't label anything a "paramountcy" on my map.

* *

*

§ 5.1 The Chesepioc, Chowanoc, and Weapemeoc

Beginning from the north, the

first chiefdom described by the Roanoke colonists was Chesepioc situated at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay—I covered them

already in part 1. Three other tribes

are briefly mentioned as neighbors of the Chesepioc: the Mandoag, the

Tripanick, and the Opossians.

"Mandoag" is probably a mistake for "Mangoag" i.e.

the Iroquoians to the west, though some disagree. As for Tripanick and Opossian: some have said

they refer to groups later found within the Powhatan paramountcy, perhaps the

Nansemonds or the Warraskoyacks.

"Opossian" does very vaguely resemble "Potcheack", a

later alias of the Nansemonds (cf. Stanard:1900), but honestly I don't think

there's anything to be found in these names.

There were several tribes and

chiefdoms whose borders ran parallel to or intersected with the Chowan River,

and in order to locate them it's necessary to identify and locate the major

settlements built along this river. On

the west bank these were Ramushouuōg,

Chowanoac, Ohanoak, Metackwem, and Tandaquomuc. A few others were located on the east bank,

but they tend to jump around a lot between maps so it's hard to know exactly

which, or how many, were on the Chowan.

This section is a little weedy with archaeological site designations,

but hopefully this map will keep things a little clear: dots are archaeological

sites, and all locations are colored blue for Colington sites or sites

otherwise associated with Algonquians, and red for Cashie/Iroquoians.

On the De Bry map, the Chowanoc town

of Ramushouuōg [some read <Ramushouuōq>

but the last letter is clearly a 'g'; for some reason Quinn suggests an

intended <Ramushonnouk>] is located on the inner corner of the

Chowan-Meherrin confluence—this corner was later termed the "Meherrin

Neck" after a group of Meherrin moved there in the 1680/90's. The Meherrin occupation is known from the

Cashie-II archaeological site designated 31Hf1 (or just "Hf1"—in

Smithsonian Trinomials all North Carolina sites begin with "31"),

however Mook and Hoffman believed that at the time of the Roanoke colony Ramushouuōg

belonged to the Chowanoc (Smith 1971:161 differs). That the Meherrin Neck had once been Chowanoc

territory was remembered by the English of Carolina during their later border

dispute with Virginia (Dawdy 1994:81) [note F].

Continuing down the Chowan River

on the west side, the next two towns of note were Chowanoac and Ohanoak—both

Chowanoc settlements. Several of my

sources agree that Chowanoac was in the vicinity of Taylor Pond creek (aka Deep

Swamp Branch?) and a cluster of sites designated Hf19, 20, 23, 24, 28, and 30 (Mook

1944:190, Petrey 2014:196, Wilson 1977:17, Mintz &al. 2011). Ohanoak was either upstream or downstream

from here, depending on who you ask. One

school of thought locates it upstream, at site Hf11. Shannon Lee Dawdy mentions that there is

"local tradition" which claims that the Hf11 area was

the location of Ohanoak, but I put almost no stock in this. The better argument for Hf11 is that it fits

much better than Br3 according to the De Bry map—this must be the reason why 20th

century archaeologists favored it (cf Wilson 1977:17).

However, Mook was critical of using the De Bry map in this way at the

expense of the supposedly more accurate written account of Ralph Lane: the

latter he says (and I agree) "clearly locates" Ohanoak downstream

near the present town of Colerain (p.191). My

other modern historical (Quinn, Hoffman, Rountree) and archaeological (Mintz et al.;

Petrey) sources concur that the Colerain area (site Br3) was the

likely location of Ohanoak.

Curiously, one important piece of

evidence is almost never brought up in the context of locating Ohanoak: the Nicholas Comberford map of 1657. This map (which is not obscure, though it is damned impossible to find an edition

with readable labels) was created using information learned from Nathaniel

Batts, one of the earliest permanent white settlers in the region—I think he's

known in NC as being the "First North Carolinan" or something. The Comberford map is one of only two maps I

know which provide fresh information on the Carolina Algonquians during the

elusive intercolonial period.

|

| Map of Nicholas Comberford, 1657. |

It's not always clear on these

old maps which tributary is supposed to be what, but there is one feature of

the Chowan River which is entirely unambiguous: Holiday Island, the little eyot

located on the first bend of the river.

This eyot isn't visible on White's map, but both the Comberford and De

Bry maps clearly show Ohanoak ("Wohanock" on Comberford) as being upstream of it. Colerain is downstream of Holiday Island.

This means that Ohanoak must've been at site Hf11,

right? Very likely... however, there is

reason to think that the village may have been relocated (they did that

sometimes) at some point between 1585 and the 1650s—see below in section §6 for

that, and for the western border of the Chowanocs.

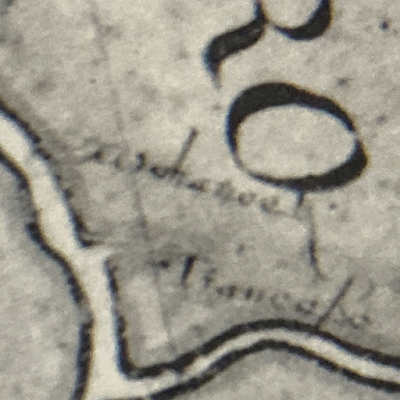

|

| "Wohanock" on the Comberford map. Taken from Cumming, The Southeast in Early Maps using my iphone and a magnifying glass. |

The Weapemeoc tribe controlled an area which in later periods was

occupied by the Yeopim, Poteskeet, Currituck, Pasquotank, and

Perquiman—although Mook questions whether all of these groups even existed, or

if some have been invented from the names of North Carolina counties. The name "Yeopim" is more-or-less

identical to "Weapemeoc" minus the Algonquian plural suffix –ak, so perhaps they had once been the

dominant (and therefore eponymous) element within the Weapemeoc

tribe/chiefdom/whatever.

I assume that the

boundary between Weapemeoc and Chowanoc territory roughly followed the boundary between the watersheds of the upper

Chowan River and the Albemarle Sound.

This border reached the Chowan River somewhere upstream from the

Weapemeoc village of Mascomenge where the city of Edenton now stands (Mintz et

al. specifically link Mascomenge to site Co30, but I can't find

anything else confirming that site's existence

much less its exact location). A few

other villages may or may not have been in the Edenton area as well, depending

on which author you ask. Several

Colington-phase sites cluster in that area, though I can't say how many were

active in the late 16th century.

Upstream a bit from Edenton

on the Chowan River are two sites: Co14 and Co15. I have not seen any archaeologist link them

to an Algonquian village, but they are in the same location as Warowtani

according to Mook, or Ricahokene according to Feest and Rountree... or they

could be nothing. Further upstream, site

Co1 has

been linked to either Warowtani or the village of Cautaking (Mintz et al.

2011:5, Petrey 2014:60). The

Comberford map shows Cautaking ("Katoking") somewhere in this area

but it's hard to tell exactly where. Quinn

critiques Mook for placing Warowtani and Cautaking so far north, saying that he

relied too much on the De Bry map at the expense of the presumably more

accurate White map. More importantly,

though, Mook's position was that if Warowtani and Cautaking were so far north,

they must have been Chowanoc towns rather than Weapemeoc. So both the pro- and the anti-Mook position would

agree that the area of Co1 and upstream of it was probably not Weapemeoc (though Co14/15 may

have been).

The Reverend James Geary

provided Quinn with an Algonquian etymology for Ricahokene ("place where

combs are made"), but I personally cannot accept this since the name is

almost identical to Rickahockan, a later tribe whose name (cognate with

"Erie") is Iroquoian for "people of the cherry tree place"

(something like [e]riʔkehakaʔ). Rather than being a village of Weapemeocs,

the Ricahokenes were a wandering Iroquoian group—they were later found in

Virginia by 1608, and subsequently fled west over the mountains (cf Hann 2006:54)

[note G]. Therefore the area

around sites Co14/15 was not necessarily

within Weapemeoc territory, but it does sound like the Ricahokene were

associated—at least politically—with the Weapemeoc chiefdom.

|

| Map of John Lederer, 1672. Note "Rickohockans" in the mountains. |

Sites Co14 and Co15 are

located on a stream called Rockyhock Creek, no doubt named for the

Ricahokene/Rickahockan; on the Comberford map the people living here are called

the "Rockahock". So it's quite

unlikely that Christian Feest is wrong in locating them here... despite the

migrations aforementioned, at least some Ricahokenes must have stayed long

enough to meet Nathaniel Batts in the 1650s.

Less secure than the Ricahokenes' location is their affiliation: if they

were a wandering Iroquoian group, then cultural and linguistic differences

might have kept them apart from the "other" Weapemeoc villages. Lars Adams, in his article on the 1670s'

Chowan River War, maps the Rockahock village within Chowanoke territory—he

doesn't elaborate on why. However, the

Chowanoc don't seem to have suffered such a disintegration as the Weapemeoc did

in the 17th century: a possible motive for the Ricahokene changing sides?

|

| Map from Adams 2013. |

The Weapemeoc also controlled

a strip of territory west of the Chowan River, including the village of

Metackwem—which I have seen connected to four different sites: Br38 (Wilson

1977:22), Br45 (Petrey 2014:60), Br49, and Br56 (Mintz et al. 2011). This strip was bordered by the Chowanoc to

the north, and to the south by the village of Tandaquomuc whose affiliation is

obscure but which Hoffman, at least, seemed confident in assigning to the

Moratucs.

Under the circumstances

I think what I'm going to do is draw the border between Chowanoc and Weapemeoc

north of Rockyhock Creek (Co14/15) and south of Co1 and Colerain

(Br3). Even if site Br3 was

not Ohanoak, it may still have been a Chowanoc site. Site Co1 is almost directly

opposite the river from Colerain, and clusters more with other Chowanoc sites

especially if you consider the waterways so favored by coastal

Algonquians. But since I'm not

entirely confident in this, I will nudge the border a little to the north, say

twice as close to Co1 than to Co14/15. "Splitting the difference" in this

way probably makes as much sense as the joke about the three statisticians who

went duck hunting, but ehhh... it is what it is.

|

| Probable village locations on the lower Chowan river. |

§ 5.2 The Moratuc, Secotan, and Pamlico

The De Bry map is the

only document which names the village of Tandaquomuc, and I think this shows

that the map can be treated as a reliable source. Theodor de Bry may have been wrong about a

village's name or location, but it seems unlikely that he'd just make one up—someone must have told him. I didn't find anyone connecting any

archaeological sites to Tandaquomuc, but it does match the location and

approximate date of site Br1 (cf Petrey 2014:60).

On the De Bry map, the

village of Moratuc is on a large oxbow bend of the Roanoke River. Hoffman's and Quinn's maps both place this on

the first big meander of the Roanoke; Mook's map places it on the next meander

upstream. This needn't worry us, because

as it happens both locations contain

Cashie-phase archaeological sites: Br5 "Sans Souci"

on the first meander, and Br7 "Jordan's Landing"

on the second. The Moratuc are supposed

to have been Algonquian, whereas the Cashie series is associated with

Iroquoians. This might compell one to

suppose that the Moratucs were actually Iroquoians [note H], or that they

were Algonquians who nonetheless produced Cashie artifacts—neither is

impossible. However, the radiocarbon

dates from Jordan's Landing most likely predate the Roanoke-era Moratucs,

perhaps by centuries, and Sans Souci seems to be rather old as well (Killgrove

2002: 48-51, Heath & Swindell 2011: 17-18; Phelps & Heath 1998:6). I take this to mean that they were once

Tuscarora villages which were later taken over by Algonquians. Or they may have simply been prime locations

to build a village on.

The town of Mequopen was

somewhere in the northern Secotan peninsula.

On the De Bry map, Mequopen seems to be in the same location where Moratuc

is on both of the White maps. However I

am suspicious of how the De Bry Map—and not

the White maps—accurately depicts the excessive meandery-ness of the Roanoke

River, so I'm not willing to just toss out the De Bry map here on the

assumption that White's maps are always superior. This may be a case where John White conveyed

corrected data to Theodor de Bry.

Mook implied that Mequopen

belonged to the Secotans, but Hoffman said it was "possible" they

were Moratuc; Quinn said they were "unlikely" to be Secotans and that

they (and the Tandaquomuc) likely "belonged to a tribe occupying the

southern shore of Albemarle Sound and the swamp-forest behind". If this is some other tribe separate from all

the rest, then Quinn's speculation here is the only indication of its existence

given by any of the authors, past or present.

For the sake of parsimony then, it's best to assume that Mequopen was a

Moratuc village. According to Hoffman,

Mequopen was just east of Roanoke River or Mackeys Creek, but everyone else

locates it on Scuppernong River, and I agree that that is what it looks like on

the De Bry map.

Since there is some

uncertainty regarding the location and the political affiliation of Mequopen, I

have drawn the eastern border of the Moratuc along Scuppernong River, even

though such rivers were seldom used as political boundaries for the eastern

Indians... more duck-hunting statisticians, I'm afraid.

*

In the fullest

interpretation, the Secotan domain

included most of the Secotan peninsula and the northern Pamlico-Neuse

peninsula, as well as Roanoke Island where Ralegh's colonists settled, and Hatteras

Island a.k.a. Croatoan of "carved into a post" fame. Like the Weapemeoc, the Secotan dissolved

into separate tribes by the late 1600s, into the Machapunga/Mattamuskeet, the

Roanoke, the Hatteras, and the so-called "Bay River-" or "Bear

River Indians".

The White and De Bry maps

show three towns in the southern, "core" Secotan region, and the

names of these towns don't exactly make sense.

Two of them—"Secoton" and "Secotaóc" per

White—appear to have the same root, only inflected with different endings (someone

suggested a reflex of Proto-Algonquian *-o·te·nayi

"town" for a toponym and a reflex of *-ote·waki "they well" for a demonym). The third town "Seco" would then be

the uninflected root, but that wouldn't explain why De Bry calls it

"Cotan". Quinn says that

White's "Seco" may have been influenced by a Dry Driver or Rio Seco from earlier Spanish maps.

Altogether I don't get

the impression that the English knew a whole lot about this area, but the

Natives here were probably the ancestors of the later Bay River Indians. Wesley Taukchiray says that the 18th

century "Bay River" was actually the modern Pungo River (p31),

but I can't find any corroborating evidence for that. No contemporary map I know of ever calls the

Pungo the "Bear River" or "Bay River": on the contrary, the

Pungo is called the "Machapounga" as early as the 1657 Comberford map.

The first map to show a "Bay River"

is Lawson's of 1709, where it's identical to the modern Bay River. In fact Taukchiray quotes a letter from 1716

which refers to "the nation called Marosmoskees living formerly in the

North of Renoque" (p56).

Assuming that Renoque is the same as Radauqua-quank (a village of the

Bear River Indians according to Lawson), then this description would make more

sense if that "Bear River" was the modern Bay, not the Pungo.

"Adioyning to this

countrey aforeſaid called Secotan," saith Arthur Barlowe, "beginneth

a countrey called Pomouik, belonging to another king whom they call Piemacum,

and this king is in league with the next king adioyning towards the ſetting of

the Sunne, and the countrey Newſiok, ſituate vpon a goodly riuer called

Neus" (Hakluyt 1600:III:250). Now

that description doesn't make a lot of sense, until you consider that what Barlowe

thought was west might've been closer to southwest. For some reason a lot of early mariners on

the Atlantic coast got disoriented this way: you can see it on some of the

maps, and elsewhere in Barlowe's account where he is describing Ocracoke Island.

The borderland between

Secotan, Neusioc, and Pamlico [=Pomouik] is so little known that you can't

really blame modern map reconstructions for not bothering to try and put

borders down. That being so, I can do

little better than to just copy Bernard Hoffman.

* *

*

There are disagreements

concerning the size and extent of the Secotan chiefdom/confederacy. While the orthodox view is as aforementioned,

there are dissenting voices which say that Roanoke, Secotan, and Croatoan were

separate. Lee Miller devotes Appendix A

of her book Roanoke: Solving the Mystery

of the Lost Colony entirely to this question, and her conclusion agrees

with the orthodox view that Secotan did include Roanoke:

"The

primary evidence ... presents a convincing picture of Wingina as paramount

leader of the Secotan, whose territory included Secota (the chief town),

Aquascogoc, Pomeioc, and the towns of Dasamonquepeuc and Roanoke at the very

least, and portions of the Outer Banks and Washington and Tyrrell Counties as

well. The evidence does not sustain a

picture of a Roanoke tribe separate from the Secotan..."

(Miller

2012:269)

Miller is here mostly

responding to David Beers Quinn (1985:44).

She doesn't specify if Croatoan was also a member of Secotan, but Quinn suggests

it was—and if he is the more minimalist of the two then perhaps it's safe to

conclude that Croatoan was a member of the Secotan chiefdom, at least in 1585. Ocracoke Island certainly seems so, at least

in Arthur Barlowe's narrative, and it's right next to Croatoan.

Another dissenting view

is that Pomeioke was a separate chiefdom, sandwiched in between Secotan and

Roanoke (who were also separate). This

is the view of Helen Rountree (2021) and Michael Oberg (2020)—to some people the

fact that these works are far more recent than the rest might mean they're more

likely to be correct, but in my view modern scholarship stands alongside earlier scholarship, not

overtop it. Without getting into the

weeds of it: my reading of the primary sources makes it clear that Pomeioke was

not an independent chiefdom; Secotan was

more plausibly independent, but Barlowe at least implies that it was not. Rountree herself inadvertently(?) gives

support for the unity of greater Secotan, in when she lists off the major

chiefdoms and their rulers (my emphasis in bold and italics):

"Croatoan: No

chief was named, which is more evidence

of its being a camp within some other chiefdom. Manteo and Wanchese came from here.

Chowanoke: The chief was Menatonon, but we cannot be

certain whether he was that group's overall chief or only chief of the upriver

towns, while Pooneno was chief of downriver ones.

Pomeioke: The chief there was Piemacum.

Roanoke: The chief was Wingina, who changed his name

to Pemisapan after his brother died (before April 1586). The brother, who governed in his absence, was

Granganimeo, and his father's name was Ensenore (who, by the rule of chiefly

inheritance, was not himself a chief).

Secota: No

chief's name was recorded.

Weapemeoc: The chief was Okisko. The satellite town of Chepanoke was governed

by an unnamed woman, so the English called it "the woman's

town.""

(Rountree

2021:81)

Huh... No chief's name recorded for Secota, you

say?...

It's worse than that

though, because the Pomeioke line should say "no chief's name

recorded" as well... except that Rountree is somehow confusing Pomeioke

with Pomouik. Both locations are named

in the account of Arthur Barlowe and it is quite clear that they are meant to

be two different places—and Barlowe is unambiguous in saying that

"Piemacum" was the ruler of Pomouik

[or "Pomovik" in the 1904 edition].

He locates this Pomouik in the same area where the De Bry map locates

the village of "Pannauuaioc".

That name, for the record, also appears via Powhatan sources in the

writings of John Smith ("Panawicke", "Panawiock") and

William Strachey ("Pannawaick"), so that gives you an idea of what

the word sounded like to the Englishmen and how they were wont to spell it (cf Barbour

1975). This is why most

people—myself included—believe that Barlowe's "Pomouik" is an error

for "Ponouik".

Rountree's confusion of

Pomouik and Pomeioke may also be why she adopts the strange position that it was

the Pomeioke—and not the Pomouik/Pannauuaioc—who were the ancestors of the

later Pamlico. Unfortunately she and her

coauthor Wesley Taukchiray choose to not give any explicit rationale for this,

so I'm forced to conclude that it's the superficial resemblance between

"Pomouik" and "Pamlico" (they both sort of go

<Pam...ik...>) compounded by the misreading of Barlowe that conflates the

Pomouik with Pomeioke.

|

| Painting of Pomeioke by John White. |

The name

"Pamlico" doesn't occur in the Roanoke documents; it comes from the

17th century, and has two variants—one with an L as in Pamlico, and one with a

T as in Pampticough. Of the two, the T

variant is probably the original. I

haven't done a comprehensive search, but the first L variant spelling I could

find in the Colonial Records of North

Carolina was "Phampleco" in a text from 1681 (vol I:228). This is preceded by several maps which use

the T spelling: "Pemptico" on the Ogilby map of 1672,

"Panticoe" on the Horne map of 1666, and what I think is "Pamxtico"

on the Comberford map of 1657—though that last one is really hard to read.

Unfortunately William

Bright's Native American Placenames of

the United States doesn't give any etymology for "Pamlico" or

"Pampticough". But it was

suggested to me by an acquaintance that it may be cognate with the word for

"river" in Nanticoke: recorded as pamptuckquah!,

peemtuk, or pèmp-tugu [note I].

This resembles neither Pannauuaioc nor Pomeioke nor any variant spelling

thereof—nay, it's a different word entirely.

This is why it's no use squinting at the names in the Roanoke documents

trying to find a resemblance.

A meaning of

"river" is plausible, since the earliest tokens of

"Pamlico" and its variants all refer to the Pamlico river, not the Indian tribe—I couldn't

find any early text which explicitly locates the Pamlico Indians prior to their

removal to the Mattamuskeet reservation.

Whoever they were they must have lived along the Pamlico river and were

later named after it—much like the Bay River Indians. This puts them in the same location as the

Panauuaioc, and since both tribes otherwise lack a counterpart across the Roanoke-Albemarle

divide, they must have been the same. One

might object that since the Pomeiokes lived along the Pamlico sound, then perhaps they could have been named after it? But contemporary maps show that the people of

that time did not conceive of the Pamlico River as gradually opening up into

the sound as one continuous body of water.

Instead, the river is depicted abruptly debouching into the sound's

western end, and anyway they didn't even call it the Pamlico Sound either, it

was just "the Sound".

|

| John Speed map, 1676. |

All of this I take to

mean that the Pomouik were the Pannauuaioc; that they were the same people as the Pamlico even though that name is at least partially unrelated;

that they were not the same as the

Pomeioke; and that both the Pomeioke and the various "Secota" towns

were under the umbrella of the Roanoke chiefdom—even if it was a

"chiefdom" in only a very loose sense.

* *

*

§ 6. The Situation in 1600

Gerald P. Smith's

dissertation on the Nottoway has a comment about the Carolina Algonquians which

caught my eye:

"The

situation found by White in the Pamlico Sound area upon his return in 1587 is

not very helpful. At this time White [...]

found it necessary to have the people of Croatan intercede for him with Secota,

Aquascogoc, and Pomiock. He appealed to

them to accept English friendship with the mutual grudges of both sides to be

forgotten. There appears to have been no

overall ruler of these towns, but simply ruled by independent town

headmen. The remnants of Wingina's

people had driven off 15 Englishmen left by Grenville after Lane's departure

with Drake and then abandoned Dasemunkepeuc.

What became of Wingina's people is unknown; they may have dispersed

among several towns or have gone to Weapemeoc.

They apparently were no longer dominant over the southern towns. The intended appropriation of any surviving

crops at Dasemunkepeuc by the Croatan suggests Roanoke abandonment of the immediate

vicinity, probably through fear of English vengeance. Any formal political tie between the northern

and southern towns seems to have been dissolved by this time."

(Smith 1971:158)

In other words, the

subregions of Roanoke, Croatoan, Pomeioke, Secota, and Aquascogoc had all been

united in 1585. But the unique character

and centripetal charisma of high chief Wingina were essential to keeping it

together, and after his murder by Ralph Lane & company, the union of greater

Secotan was shattered.

It is appealing in this

view to see Wingina as a counterpart to his contemporary Wahunsonacock of

Powhatan: both chieftains in the process of nationbuilding, of absorbing and

uniting many different local chiefdoms into one overarching paramountcy. It was said that the Powhatans modeled their

political institutions after the Piscataway, and the Piscataway modeled theirs

after the Nanticoke. And note that the

Chowanoc chiefdom was more powerful, centralized, and resilient than the others

of Algonquian Carolina. Clearly the

whole "paramount chiefdom" thing was in the process of spreading

southward in the 1500s. The Secotans may

have been next in line? Perhaps if

Wingina had had a successor strong enough to fill his shoes—an Opechancanough

to his Wahunsonacock—then the process could have continued. But that didn't happen.

Why does this matter? Because remember, my main goal here is to

make a map for circa 1600, not 1585. So

how had things changed by then?

Unfortunately I can't appeal directly to anyone else's work; no one else

has asked what the Carolina Algonquian territories were in that specific year,

and why would they? So in this section I

have to do some theorizing, hypothesizing, and speculatizing of my own—it is

unlikely that all of it will be correct.

The narrative of Francis

Yeardley describes visits to and by the Roanoke in the years 1653 and '54 (Salley 1911). His account makes it clear that the chieftain

of Roanoke controlled more than just the island at that point—in fact he's

described in the text as the "emperor" of Roanoke, being an exception

to the aforementioned naming trend.

Unfortunately it's not clear which parts of the mainland his chiefdom

contained: the text almost makes it sound like it included the waters of the

Currituck Inlet, which might be wrong. But

doubtless it at least included the mainland adjacent to the island—which is to

say that the Roanokes had regained control of Dasamonquepeuc, likely decades since. Yeardley mentions several "great

men" of the "provinces" in ways which imply that the Roanoke ~empire~

at this point was more an alliance of local chiefdoms. This would be consistent with what apparently

happened with the Weapemeoc.

Gerald P. Smith's map depicts

the remainder of the Secotan chiefdom as a single "sociopolitical

unit" circa 1607. In other words,

he apparently doesn't think that Croatoan, Pomeioc, Aquascogoc, and Secotoac

etc. had all gone their separate ways after the death of Wingina—though there's

no saying what manner this "sociopolitical unit" was, if he's

right. Minus the Croatoan, that area is

roughly equivalent to the later haunts of the Mattamuskeet/Machapunga and Bear

River Indians—both groups together are at least sometimes referred to as

"Mattamuskeet", and I will opt to label them thus on my map. I could call them "Secotan" but

then—if I ever make a chronological map—that would open the pointless question

of exactly when they stopped being Secotans and started being Mattamuskeets.

* *

*

The country to the west

of the Chowan river also underwent changes in the intercolonial era, being a

theater of war between the Chowanoc and the Tuscarora. Presumably the Moratuc too were involved.

The entire strip

adjacent the river, from Ramushouuōg to the mouth of the Roanoke, was in the

hands of the Algonquians in the 1580s.

By 1644, however, the situation had changed: at that time, during the

Third Anglo-Powhatan War, members of the Weyanock chiefdom broke away from the

Powhatans and fled south into North Carolina, settling in the country west of

the Chowan. This historical event ended

up being relevant to a boundary dispute between Virginia and Carolina, and in

the early 1700s several depositions were taken (from mostly elderly Englishmen,

Nansemonds, Meherrin, and Chowanoc) regarding the details, later collected and

published as The Indians of Southern

Virginia in 1900. The deposed

witnesses mostly agreed that when the Weyanocks migrated south they purchased

the territory west of the Chowan river from the Tuscaroras (not from the Chowanoc,

Weapemeoc, or Moratuc). The Algonquians

had evidently all been driven out (cf Parramore 1982:311).

How much of this strip

was actually overtaken by the Tuscarora, and when did this conquest take place? The tract bought by the Weyanocks was said to

have extended from the Roanoke River to the mouth of the Meherrin—however, some

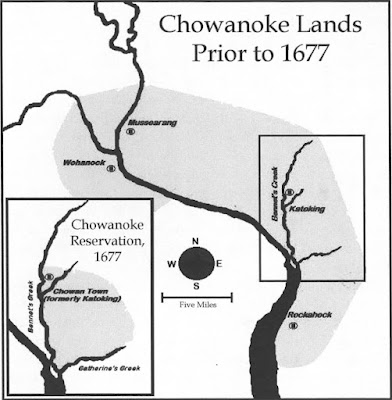

statements in the depositions suggest that it only went up to Wicacon Creek. Subsequent events show that the Chowanoc

still controlled the land above this

creek until their defeat in the Chowan River War of 1676-7 (Adams 2013). Recall that the Comberford map shows that the

town of Ohanoak still existed along the upper Chowan river in 1657. If the Tuscaroras had invaded the lands below

Wicacon Creek, then the Chowanoc would have fled upstream. And if Comberford's "Wohanock" was

as far upstream as Lars C. Adams believes it was (too far to be at site Hf11), then

the village may have been relocated—perhaps from the Br3/Colerain

area. The absence on the Comberford map

of Chowanoac, Metackwem, and Tandaquomuc suggests that these towns too had been

destroyed or forced to relocate.

The Englishman John Pory

visited the Chowanocs in 1622, and although his own account is not available, other

writings refer to him crossing south of the Chowan river and visiting the

"Choanoack" (Powell 1977:100).

Assuming that to be the town and not just a reference to the tribe in

general (they are in fact the same name), then this means that Chowanoac was

still standing at that time. It probably

wasn't directly threatened until after 1632,

when the Powhatans lost their second war with the English and had to reduce

their support for the Chowanoc against the western Indians (Parramore

1982; he writes "1622" but it looks like an error for 1632). However, the Tuscarora invasion had likely

already been progressing by then.

Remember how I said that

the Comberford map is one of two maps that show fresh information for the

post-Roanoke, pre-Albemarle period? Well

the other such map is the so-called Smith/Zuñiga map of 1608. Its exact provenance is a little unclear, but

it may have been copied from an original map by John Smith. The information on the map came from

Powhatan-speaking sources, and the names it uses for the North Carolina area

tend to differ from the names we've been using and therefore aren't very

helpful (the reverse is also true: John White's map using Carolina Algonquian

names for the Chesapeake Bay region).

The geography isn't very good either, but you can at least make out the

Chowan, Roanoke, Pamlico, and Neuse rivers.

People usually bring

this map up because one of the captions seems to say what happened to the Lost

Colonists. But another caption shows a "morattico"

on the southern shore of Pamlico River: far from their location 20 years

earlier. This might just be a

mistake. But on the 1657 Comberford map

a "Morataux" is shown on Bennett's Creek north of the Chowan—which is

also a completely "wrong" place.

So maybe these aren't mistakes, and the Moratuc were in fact a

dislocated and wandering people. The

conclusion then is that by 1608, the Tuscaroras had already driven the Moratucs

from their former lands on the Roanoke River.

To this I might add that the Tandaquomuc region is one of the plausible

locations for the Lost Colonists to have relocated after 1587: a biological

bomb planted in the heart of Moratuc country?

|

| Hidden icon of a fort on John White map. Picture from Artnet News. |

Lost Colonists or no

Lost Colonists, though, the balance of the region could have been destabilized

by the whole Roanoke venture and the death of chief Wingina. If so then the dispersal of the Moratucs was

likely sooner rather than later within the 1586-to-1608

interval. I'm guessing the Tuscaroras

had already descended the Roanoke by 1600.

These hypotheses are

wide open to criticism. I have to grasp

at whatever straws I can find to try and date the changes that happened in the

intercolonial period. Two especially

tenuous assumptions I make here—1: that the northwest of the Secotan peninsula

was repopulated by the Roanokes after the dispersal of the Moratucs; and 2: that

the western border of the Algonquians in 1585 was also the border of the

Weyanock land grant in 1644 (assuming also that the town of

"Towaywink" on the Roanoke river where the Weyanocks settled was in

the same location as the old town of Moratuc in 1585). These make intuitive sense to me but are really

no more than guesses.

|

| Conjectural reconstruction of the Tuscarora conquest of the Chowan. |

* *

*

§ 7. The Southern Periphery: Neusiok and Coree

The Neusiok are the last and southernmost Algonquian group in North

Carolina. Or rather, they might be—calling them Algonquians tends

to be accompanied by an implicit little tap on the nose, since the Roanoke

colonists didn't interact with them at all and there is in fact no evidence

whatsoever for what kind of language they spoke. The same is true, or nearly so, for the Coree who were the next Indian group

south of the Neusiok—the Coree inhabited the coastlines of Core Sound and Bogue

Sound, and probably some distance further though here our knowledge gradually

fades into smoke.

It's difficult to say much with

certainty about either the Coree or the Neusiok. Neither tribe is well known

historically: they appear in the records

of the Roanoke colony although as far as I know they had no contact with them,

and later they occupied minor roles in the Tuscarora War and events leading up

to it. Not long after the war both

groups disappear from the historical record, and consequently not a whole lot

is written about them. A couple modern

books devote a few pages each to the Coree: Brandon Fullam's The Lost Colony of Roanoke: New Perspectives

(2017:

pages 78-81) and David La Vere's The

Tuscarora War (2013: pages 58-9).

Together with bits of Mook's article these are the fullest treatment of

Coree history I know—even the Handbook of

North American Indians allots them only a couple of lines.

The Coree went by a few

names. "Coree" itself was also

spelled "Core" and it's not certain which spelling better reflects

how the English pronounced the name: the modern local pronunciation in

placenames like "Core Sound" is as one syllable (Goddard 2005:n33). To the Roanoke colonists they were known as

the Cwareuuoc, which is Algonquian for "the people of Core"—Goddard

suggests something like kwa:ri:wak. The same <cor> root is found in "Coranine"

which is the name they went by in the late 1600s. That is how John Lawson usually referred to

them, however in one place in his book he clarifies that Coranine (and Raruta)

are merely names of villages, and

that the entire tribe is called Connamox. The latter name pops up in another document

from 1703 as "Connamocksocks" which is the same plus a couple extra

Algonquian and English plural suffixes (Taukchiray 1983:30) [note J].

|

| "The Coranines" on Neuse peninsula on the Comberford map. As far as I know it is the first attestation of the name "Coranine". |

The Neusiok and Coree territories

seem to have been undifferentiated by around 1700. Around that time both tribes had villages

within the diamond between the Neuse and Trent rivers—one Neusiok village named

Chatooka in the eastern corner where

the town of New Bern was later built, and two presumably Coree towns named Coram

and Corutra upstream on the Neuse. One

of those may have been the same place otherwise known as Core Town, located somewhere on the Neuse between New Bern and the

embouchure of Catechna Creek [note K]. In

1709 John Lawson records Coranines at the tip of the Neuse peninsula

overlooking Cedar Island, and a Neusiok village Rouconk which may have been approximately where the earlier Neusiok

town of Marasanico was located (Mook 1944:219).

|

| John Lawson map, 1709. |

Lawson's book also has this

peculiar passage:

"This Morning, we ſet out

early, being four Engliſh-Men,

beſides ſeveral Indians. We went 10 Miles, and were then ſtopp'd by

the Freſhes of Enoe-River, which had

rais'd it ſo high, that we could not paſs over, till it was fallen. I enquir'd of my Guide, Where this River

diſgorg'd it ſelf? He ſaid, It was Enoe-River, and run into a Place call'd Enoe-Bay, near his Country, which he

left when he was a Boy ; by which I perceiv'd, he was one of the Cores by Birth : This being a Branch of Neus-River."

(Lawson 1709:58)

This only makes sense if we

assume the middle-lower Neuse river was considered part of the Eno river,

contrary to the modern hydronymy. Still

though, why did he conclude his guide was Coree rather than Neusiok? The disgorgement of the Neuse river is much

closer to the two Neusiok villages than it is to either Core Town or the Core

Sound. This is also the only place in

his book where Lawson refers to the tribe in question as "Cores", as

opposed to Coranines or Connamox. It's

almost as if he considered "Core" to be a broader category including

both the Coranines and the Neusioks?

However, Chatooka was still a

relatively new installment as of 1710, when the Baron von Graffenried bought

the land from the Neusioks to build his settlement of New Bern—according to

Mook, those Neusioks had only recently moved from the southeast; Fullam and La

Vere say the same of Core Town. The maps

of White and De Bry, such as they are, also show an apparently more clear-cut

division between the Neusiok and Coree territories. Thus the situation around 1700 was not what

it had been in 1600 or 1585.

* *

*

The Coree and Neusiok languages

are completely unattested and—since they were hemmed in by the Algonquians to

the north, the Woccon to the northwest (who were Siouan, or specifically

Catawban), and by various Carolina tribes to the southwest (whose languages are

unknown)—it's difficult to even guess at what their languages were like. One sometimes sees an author state authoritatively

that they definitely spoke

Algonquian, or that they certainly

spoke Iroquoian, or that it's a sure

thing they spoke Siouan... but this is bullshit. The only real evidence we have is this

statement from John Lawson:

"I once met with a young Indian Woman, that had been brought from

beyond the Mountains, and was ſold a Slave into Virginia. She ſpoke the ſame

Language, as the Coranine Indians,

that dwell near Cape-Look-out,

allowing for ſome few Words, which were different, yet no otherwiſe, than that

they might underſtand one another very well."

(Lawson 1709:171)

I agree with Ives Goddard that

this implies the Coree language was distinct from Tuscarora, Woccon, and

Carolina Algonquian, though I don't share his confidence in Lawson's linguistic

abilities that it "must indicate" as much (2005:22). If this language from "beyond the

Mountains" were something like, say, Cherokee (Iroquoian) or Biloxi

(Siouan), then it would have sounded incomprehensible to even a fluent speaker

of Tuscarora or Woccon. And since he

doesn't give any examples, unfortunately John Lawson is of very little use to

us.

Nor does archaeology help. The entire coast of Onslow Bay from the Neuse

to Cape Fear rivers was occupied by people represented by the archaeological

Oak Island (aka White Oak) phase, which is very similar to the (Algonquian)

Colington phase. Both Coree and Neusiok

left Oak Island/White Oak artifacts, so this might mean that they were in fact

Algonquians. Brandon Fullam cites

"local historical tradition" (by which he means the Swansboro Chamber

of Commerce website) that the town of Swansboro on White Oak River was built

over the ruins of an old Algonquian village—this is farther south than any

known Coree location. Even further south,

three archaeological sites (On196, On305, and On309) show signs

of Algonquian habitation in the 13th and 14th centuries (Killgrove 2002:44-8,

Loftfield 1990).

The similarities with the

Colington-phase may indicate that the Oak Island-phase represents an extension

of Algonquian-speakers south past the Carolina Sounds, however some

archaeologists believe these similarities are due to a Siouan population adopting

northern traits. On the other hand, the

assumption that the Onslow Bay coast was inhabted by Siouan speakers at all is,

I believe, based on some dubious assumptions [note L].

The rub is that the border

between the Neusiok and the Coree, as well as the border between the Coree and

their southern neighbors, are archaeologically invisible, since all three

groups left Oak Island-phase artifacts.

The maps of modern authors—Speck, Mook, Quinn, Binford, Hoffman, Smith,

Feest, and others—are also pretty inconsistent in their placement of both

tribes. I've followed Hoffman's map in

assigning some Neusiok territory to the north of Neuse River (though I fear

this may be influenced by their later northernish habitation of Chatooka). Learning more requires locating the villages

of Cwareuuoc and Newasiwac on the maps of White and De

Bry.

John White's map doesn't name the

Cwareuuoc, however there are two unlabeled dots located on Core Sound which may

correspond to De Bry's Cwareuuoc and

the unnamed village next to it. David Beers Quinn suggests that this unnamed village was

near Mansfield, west of Newport River.

Later maps continue to show Neusioock and Cwareuuock but offer no real insight on their exact location (see note

M). David Beers Quinn and Bernard

Hoffman both located them like so:

These are in the same places as

two known archaeological sites: "Neusiok" corresponds to the Garbacon

Creek site (Cr86) and "Cwariooc" to the Broad Reach site (Cr218) (Killgrove

2002). The dating and culture of

Garbacon Creek is more-or-less consistent with a Neusiok affiliation. Broad Reach has Algonquian and Siouan

influences, leaning towards Algonquian, and is too early to cleanly be De Bry's

Cwareuuoc but it may have been

inhabited by different people at different times—at the very least it tells us

that it was a good place to build a village.

I find the Quinn and Hoffman locations especially interesting because—as

far as I know(?)—both archaeological sites were not excavated until after their studies were published...

although I don't know, maybe they had heard from somebody that something was there.

Another site that's in an

interesting location is Piggot Ossuary (Cr14), located at Gloucester, where

the Neuse peninsula comes closest to the pointy bit of Cape Lookout (Killgrove

2002, Loftfield 1990). This may

have been one of the two "Connamox" villages that Lawson wrote about:

Raruta and Coranine proper. La Vere and

Fullam both cite sources to this effect, though I can't get ahold of them to

double-check. La Vere's source favors

Coranine proper for the Gloucester locale.

Fullam's source suggests that Raruta was to the west, past Newport

River—the same location as De Bry's unnamed village according to Hoffman, and

White's unnamed village according to Quinn.

Between Lawson's comments, the

historical maps, and the archaeological digs, it's hard to say exactly how many

Coree settlements there were here and whether any of them moved and/or changed

names between 1585 and 1709. But in

general they seem to have inhabited the shore at least from Gloucester to White

Oak River. For the 1600 period I'm

assuming that the Coree-Neusiok border just ran along the length of the Neuse

peninula.

.jpg) |

| Fun fact: The area in and immediately surrounding the Coree homeland is the only place in the world where you find wild Venus fly-traps. |

The "other" Coree

village on Core-Bogue sound—the unnamed dots on the White and De Bry maps—may

have had the name Warreā. This is implied by a label on the so-called

"Sketch Map" of 1585, drawn by an anonymous member of the Roanoke

colony. Quinn proposes a connection

between this and a document from 1586 which shows that the Roanoke colonists

were familiar with an otherwise-unattested "Waren" river. Another explanation is that Warreā is just the same as Cwareuuoc only with the "k"

sounds dropped for some reason.

I want to point out a possible

connection also with the name of the White Oak River. One might think that this river was named

after oaks which are white, but in early documents the river and its Native

inhabitants are referred to as the "Weetock". This is far too unusual to just be a variant

spelling of "white oak", and the –ock ending in particular makes it

look like an Algonquian plural noun.

Indian names being reanalyzed in this way isn't unheard of (cf. Tawakoni

> "Trois Cannes", or [Cree] Wīsahkēcāhk > "Whiskey

Jack").

There are two faint indications

that the territory of the Coree may have extended as far south as Cape Fear

River, thus encompassing all of the non-Neusiok area of the Oak Island archaeological

phase. One is in an article by Blair

Rudes wherein he suggests a connection between the Coree and the so-called

"Chicora" of the Ayllón

expeditions (Rudes 2003). Chicora is

usually supposed to be further to the south, but Rudes' analysis of apparently-Tuscarora

words in the Ayllón documents puts it within the range of the general Coree

area. More specifically, Rudes mentions

an old Spanish map [he doesn't say how old, nor afaict do his sources] on which

the Cape Fear River is called the Rio

'Chico'. The presence of quotation

marks around the word "Chico" suggests to Rudes that this was a name,