[This is part 2 of a 2-part series of posts

about the identity of the Quiohuan Indians.

Click here for part 1.]

So... why do

I not think that the "Quiohuan", who show up in several documents

from 1687 to 1719 as a tribe living in or near eastern Texas, were the same people as the Kiowa? If you've read part 1 (please do so before reading this) you might think it's because, according to James Mooney's telling of Kiowa history, the Kiowa were located too far to the north prior to 1775 or so. And you would be right, that is an important

reason. As historian William Newcomb put

it:

"Mooney (1907, Volume I:701) identifies

them [the Quiohuan] as Kiowas, an improbable speculation since the migration of

Kiowas into the Southern Plains did not occur until almost a century

later." (Newcomb 1993)

But the

truth is, it's more complicated than that.

Mooney's Calendar History is

not exactly an obscure text in this field: of

course the scholars who support the Quiohuan=Kiowa hypothesis are already

well aware of it. It's no secret to them

that the Kiowa formerly resided in the Northern Plains and the Kiowa

Mountains. They already know. I mean, look at that Newcomb quotation again:

who is it he says first identified the Quiohuan as the Kiowa? James

Mooney. Mooney may have been

wrong—about many things—but one thing you can't accuse him of is being unaware

of his own prior research.

So why do

scholars [most that I've seen, at any rate...] think that the Quiohuan were the Kiowa regardless? Well, to be honest I'm not entirely sure,

because I don't often see them explicitly argue the point: usually they just...

assert it, and move on. But I can

think of a few possible arguments one could make in defense of the Quiohuan=Kiowa

hypothesis.

Argument

#1: The Kiowa actually do originate in the Southern Plains,

despite all that stuff I wrote in Part 1.

There have been scholars who have questioned the accuracy of Mooney's

version of Kiowa protohistory. Robert

Lowie, an expert on the Crow Indians, specifically attacked the idea that the

Kiowa had once enjoyed a long and close relationship with the Crow:

"Since Mooney's thesis rests on

tradition, I ought to premise that while the briefest of stays with the Kiowa

sufficed to corroborate that the story is indeed part of their folklore, I

never once heard the Crow refer to the Kiowa in this connection, though I spent

seven or eight field sessions with them[...]

As for the Kiowa, they play so slight a figure in Crow thought that

though constant mention is made of the Hidatsa, the Dakota, the Cheyenne, the

Shoshone, and the Piegan, references to the Kiowa hardly ever occurred during

my visits." (Lowie 1953)

That is a

very interesting point—enough indeed to throw doubt on the accuracy of Mooney's

narrative—and I take it very seriously.

However, as Lowie also notes:

"Two questions must be distinguished

here—the [Kiowas'] earlier residence in the north and the specific affinity

with the Crow." (Lowie 1953)

Indeed.

"As for the former, what is involved is

of course not whether the ancestors of the Kiowa, along with other Indians,

came from the north ten thousand or five thousand years ago; the question is

whether in, say 1500 AD, they had their home in western Montana or, as has been

alleged, even in the neighborhood of the Sarsi; whether their occupancy of the

southern Plains falls into a very recent past.

On this point, I have no new observation to offer: I merely accept whole-heartedly

the suggestions made by Wissler and Kroeber, viz. that the tribe has been in

the region of the Canadian and Arkansas Rivers for a considerable period; that

their presence in the north 'may have been due to their periodic wanderings'

(Wissler); that after a temporary sojourn in the north they returned to their

southern habitat, 'legend retaining only the last of the events'

(Kroeber)." (Lowie 1953)

I like the

Mooney narrative because it's thorough and precise and it has a lot of

dates. But it's true that precision and

accuracy aren't the same thing, and I don't really have the scholarly toolset

to evaluate how reliable it is: all I can do is rely on what the experts

say. And while it's interesting to learn

that Clark Wissler and Alfred Kroeber both believed the Kiowas' northern

residence to be a temporary interruption of a more permanent residence in

the south... it is my distinct impression that modern experts have come to

agree with the Mooney narrative, at least in broad terms. Wissler and Kroeber were working during a

time when the Kiowas' northern origin was still an anomaly, when archaeologists

thought that the Fremont culture represented the early Apache. Scott Ortman makes (what seems to me, at least) a strong case for the Proto-Kiowa being in the Fremont area... or, if not

there, then at least at the northern end of a Kiowa-Tanoan dialect chain

extending north from the Colorado Plateau.

From that point, it's a matter of simple geometry to explain how they ended

up in Montana.

Argument

#2: The Kiowa were found in the east Texas region in 1687-1719, but they didn't live

there—they were just visiting ("visiting") from the north. There's a lot to be said for this

argument. It is true that the Kiowa in

historic days were incredibly mobile.

Mildred Mayhall says that Kiowa raiding parties could range as far and

wide as the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf of California, and Canada. One raiding party allegedly went as far as Belize (British Honduras), which I find

a little incredible...

Furthermore,

it's a matter of record that Kiowas did occasionally wander as far south as

New Mexico in the early 18th century.

Spanish records from the 1730's onward report groups of "Caiguas" (etc.) pillaging

New Mexico settlements alongside Ute, Comanche, and Apache raiders. And David Brugge even found references to a Kiowa burial as early as 1727 in the church records of New Mexico (Brugge 1965). This fact alone would seem to belie the

notion that the Kiowas were too far away to have been the

"Quiohuans": if they could travel to New Mexico in the 1720's, what's

to stop them from traveling to the east end of Texas as well?

Two

responses to that. Firstly, the Kiowa as

they appear in the 18th century New Mexico records all share an important

dissimilarity to the Quiohuan, but I'll get back to that later. Secondly—and I could be wrong here—but it's

probably safe to assume that the Kiowas' globetrotting habits of later eras

were enabled by the acquisition of the horse.

Presumably they didn't walk to

Belize... and I suspect they didn't walk to Texas, either. Much has been written about how the

acquisition of the horse upturned Plains Indian culture in just about every

conceivable way. Mooney expressed it

rather picturesquely:

"It is unnecessary to dilate on the

revolution made in the life of the Indian by the possession of the horse. Without it he was a half-starved skulker in

the timber, creeping up on foot toward the unwary deer or building a brush

corral with infinite labor to surround a herd of antelope, and seldom venturing

more than a few days' journey from home.

With the horse he was transformed into the daring buffalo hunter, able

to procure in a single day enough food to supply his family for a year, leaving

him free then to sweep the plains with his war parties along a range of a

thousand miles." (Mooney 1898:161)

I know of no

references to the Quiohuan from before 1687 (see below). That seems rather early, to me, for a tribe

of southern Montana to have already acquired and mastered horsecraft. It's not impossible—the Rocky Mountain

Shoshone and Flatheads had horses by about 1700 (Hämäläinen 2003)—but I find it

unlikely. The Kiowa told James Mooney

that they didn't acquire horses until after they moved east of the Crow and

settled in the Black Hills, which Mooney estimated was after 1700. And, without the use of horses, I think it's

also unlikely that the Kiowas could have performed long-distance raids as far

south as Texas back in the 1680's. It's

also worth pointing out that the first

definite reference to the Kiowa in the New Mexico records postdates the last reference to the Quiohuan by nearly a

decade.

Argument

#3: It is true the Quiohuan were not in

east-central Texas in 1687-1719, nor even in Oklahoma, but then again no one

ever claimed they were. This argument

also has merit. Older maps appear to

show the "Quiohouhahan" etc. somewhere in Texas or maybe Oklahoma (or

maaaybe Arkansas), but the geometry

of those maps is very confused. For

example, they also tend to show the source of the Rio Grande as just a short

distance due west of Minnesota. I don't

know what Delisle's sources of information were for the upper course of the Red

River, Trinity River, etc... he may have just been guessing, for all I know.

A better way

to interpret the early maps is as just saying the Quiohuan were some undefined

distance inland. And the contemporary

documents which mention the Quiohuan may have only been reporting rumors of a

tribe located much farther into the interior than the authors themselves ever

ventured... maybe even as far as MT/WY/SD?

Is that possible?

Maybe. But I don't think it's probable. This is probably a good time to discuss the

documents themselves.

* * *

The first

time I'm aware of when "Quiohuan" (etc.) appears in writing is in the journal of Henri Joutel in 1687.

Joutel was among the Caddo at the time, staying in a Kadohadacho

("Cadodaquis") village in what is now the extreme northeast corner of

Texas:

"Now the chief often named the nations

for me, their enemies as well as their allies, and he named some I had heard

formerly from La Salle, and this pleased me.

I took the names of these nations and wrote them down so I could recall

them.

These tribes are their enemies:

Cannaha, Nasitti, Houaneiha, Catouinayos,

Souanetto, Quiouaha, Taneaho,

Canoatinno, Cantey, Caitsodammo, Caiasban, Tahiannihouq, Natsshostanno,

Cannahios, Hianogouy, Hiantatsi, Nadaho, Nadeicha, Chaye, Nadatcho, Nardichia,

Nacoho, Cadaquis, Nacassa, Tchanhe, Datcho, Aquis, Nahacassi

These tribes are their allies:

Cenis, Nassoni, Natsohos, Cadodaquis,

Natchittas, Nadaco, Nacodissy, Haychis, Sacahaye, Nondaco, Cahaynohoua, Tanico,

Cappa, Catcho, Daquio, Daquinatinno, Nadamin, Nouista, Douesdonqua, Dotchetonne,

Tanquinno, Cassia, Neihahat, Annaho, Enoqua, Choumay" (Joutel 1998[1684-7]:246)¹

The second

time is from a letter written in Spanish by Fray Francisco Casañas in

1691. Casañas had spent about a year

preaching the gospel among the Hasinai and Kadohadacho:

"The enemies of the Province of the

Áseney [Hasinai] are the following: Anao, Tanico, Quibaga, Canze, Áyx, Nauydix,

Nabiti, Nondacau, Quitxix, Zauanito, Tanquaay, Canabatinu, Quiguaya*, Diujuan, Sadammo." (Casañas 1927[1691])

(* - In one

of the printed editions, this name is spelled "Quiguayua".)

Then by 1716 (at least), the name begins to appear on French maps of North America. The mapmaker, Guillaume Delisle, had access to the journal

of Henri Joutel (Foster 1998:26), so his maps might not be an independent witness. However, as far as I know Delisle could not

have learned about the Yojuane ("Ionhouannez") from Joutel or anyone

else I'm aware of, so he may have had other sources of information.

The next

appearance is in 1717, in the "Declaration" of Louis Juchereau de St.

Denis. St. Denis was a French trader and

explorer who had spent time among the Natchitoches and the Hasinai. The document (written in Spanish, and by a

third party, which is why St. Denis is referred to as "he") reads:

"To the east of the Tejas [Hasinai] is

the Natchitoches nation on the Colorado [=Red] River, which empties into the

Mississippi. Those which are to the

north, northwest, and west of the Asinais are the nation Yojuan, the Tancahoe, the Quihuugan, the Guanetjaa, the

Nodacao, the Quitzais, Saccahe, Nauittij, Canohatinoo, Conux, Tahoangaraa,

Cahineo, and there are others whose names he does not remember. He [St. Denis] knows of them from what he has

heard the Tejas say and by reports which they themselves have heard. These nations do not have villages nor fixed

abodes because of fear of the Apaches." (St. Denis 1923[1717])

The next is

from 1719, from the journal of Bénard de La Harpe's exploration of the Arkansas

River. La Harpe had sent his aide, a M. Du

Rivage, on a reconnoitering expedition up the Red River:

"...he reported to me that at seventy

leagues by land to the westward and from the west a quarter northwest, he had

encountered part of the nomadic tribes, which are Quidehais, Naouydiches,

Joyvan, Huanchané, Huané, Tancaoye, by whom he had been very well received.

[...] These nations are allied with that of the Quiohuan, situated at two leagues from the Red River, on the

left, in going up to the environs of the place where M. Du Rivage had found

these nomadic nations." (La Harpe 1958[1718-20])

Daniel

Prikryl (2001)

locates Du Rivage's encounter in the area around Lake Texoma, Texas.

The next

time the name appears is in an anonymous document entitled Mémoire sur les Natchitoches (in Margry V6:228). The text is undated, but according to

Gunnerson & Gunnerson (1971) was written shortly after 1718:

"The nations which are near [the Red

River], or which are established on its course, from its mouth to the places

known to us, are the Aouayeilles, the Innatchas, the Quiouahans, the Touacanna or Paniouassas; these are near the

River of the Otouys." (in Margry 1886 (Vol 6):228) [via Google Translate]

The last

time the name appears is in a work by Baudry des Lozières: Voyage a la Louisiane, et sur le Continent

de l'Amérique Septentrionale, written from 1794 to 1798. This one can probably be discounted; I

explain why in footnote 2.

Those are

all the examples I could find of the Quiohuan being named in the historical

documents. There may be more

examples—real-life historians who work with physical manuscripts might be able

to find some—but for right now, that's all I got.

These

documents all name the Quiohuan as either enemies or neighbors of the Caddo, or

as allies or neighbors of the Wichita.

The Caddo and Wichita often fought each other, so the politics are

consistent, one anomaly being the "Naouydiches" (etc.) who are called by a Caddo name (Nawidish - "Salt Place") even by Du Rivage's informants who, presumably, spoke Wichita. Among the other tribes named that can be

identified, most are either Caddo groups or groups reasonably close to the

Caddo, such as Natchezan or Wichitan tribes.

The most distant outliers (again: that can be identified) are the

Kansa (eastern Kansas) and the Tonkawa (northern Oklahoma, at most).

Any tribe

from the north of Kansas—much less the plains west of the Black Hills—would be

a very distant, oddball outlier on these lists.

That makes it unlikely that the "Quiohuan" were a tribe

situated that far north, who were only known about second-hand. In combination with the La Harpe account and

the anonymous Mémoire³—which locate

them in north-central Texas and northwest Louisiana—it also makes it unlikely

that the Quiohuan were a northern tribe who only made seasonal raiding

appearances in the south. That eliminates Arguments #2 and #3. Since almost all the other tribes named in

the primary sources are southern tribes, it's reasonable to assume that the

Quiohuan were a southern tribe as well.

Which means that they were not Kiowa.

However,

that's not even my main reason for doubting the Quiohuan=Kiowa hypothesis. My main reason is the simple observation that

"Kiowa" and "Quiohuan" don't even look like they are the

same name... not after you take English's unusual vowel spelling into

account. The name "Kiowa" is pronounced in English more or less like [kaiowa] or [kaiawa].⁴

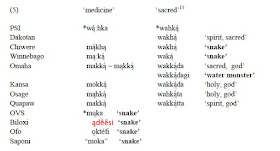

The various times that the Kiowa are mentioned in Spanish colonial documents from New Mexico:

Cahiaguas,

Cahiguas, Caihuas, Cargua [supposedly a

misprint for *Caigua], Cayouas, Caigua, Caygua, Cahihua, Caiua, Cayba,

Caiba, Cayga

[source: Mooney (1898) and Brugge

(1965)]

...all seem

to represent a similar pronunciation: something like [kaiwa].⁵ The English and Spanish forms are relatively

straightforward renditions of the name as found in various Native American

languages:

Káhiwaʔ (Caddo),

Káhiwaʔa (Wichita), Kahíwa (Kitsai), Káʔiwa (Pawnee), KaʔíwA (Arikara),

Kaiwa~Kaiwɨ (Comanche), Kkáðowa (Osage), Kkáʔiwa (Kansa and Ponca), "Gaiwa" (Omaha), Kaíwa (Oto), Kaiwah (Shoshone), Gáiwa

(Towa)

(other languages use names that

are completely unrelated)

[source: Handbook of North American

Indians Volume 13(2)]

These are

all pretty consistent—usually [kaiwa], [kahiwa], or [kaʔiwa]—making the

question of which language English and Spanish borrowed the name from

irrelevant.

Now, on the

other hand, the various spellings of Quiohuan:

in

French:

Quiouaha,

Quiohouhahan, Quiohouan, Quichuan [for

*Quiohuan], Quiohuan, Quiouahans

in

Spanish:

Quiguaya

[or maybe *Quiguayua], Quihuugan

...all look

like attempts at spelling something like [kiwa] or [kiowa] (or possibly [kiwaą]

or [kiowaą]). I think this is a different name. There appear to be two

separate names here: one, a kai-

name, definitely referring to the Kiowa each time it appears; and another, a kio- name, which only ever refers to a

tribe in/near east Texas... in what would be an unusual place and time to find the Kiowas. The visual similarity between the names

"Quiohuan" and "Kiowa" is the only reason anyone believes

in a Kiowa-Quiohuan connection in the first place (and not in, say, a

Kiowa-Canohatino connection). But if the

two names are not in fact the same,

then that leaves no more reason to believe that the Quiohuan were the Kiowa.

Is it wise

to be this literal in interpreting colonial-era spellings of Indian names

phonetically? Individually: no. Europeans were barely consistent in spelling

their own languages in the 17th-19th centuries, let alone the languages of

North America with their glottal stops and lateral fricatives and so on. Individually: it's more likely that a

European, upon hearing a word in an Indian language, would inadvertently

distort it in some way (either by mishearing it, misremembering it, or just

being sloppy in writing it down).

But we're

not dealing with an individual

attestation of a name—we're dealing with

about twenty. It's one thing to say that

the name was distorted... it's another to say that the name was distorted

multiple times in exactly the same way

each time. Furthermore, the

difference in orthography corresponds exactly to the difference in geography:

all of the kio- names come from the

region around east Texas, and all of the kai-

names come from outside it. Mathematically,

it's highly unlikely this would happen by chance. There are only three ways one could wave away

this anomaly.

One way is

to say that the name [≈kaiwa] wasn't distorted numerous times into [≈kiowa]—rather,

it only happened once. Like a genetic

mutation that only has to happen one time and then gets inherited by all of the organism's descendants, maybe there was one initial French writer (Joutel in this case) who rendered

the name as "Quiouaha", and then all later writers were just copying

him. On its own merits, this explanation

seems unlikely. Delisle and Beaurain

were copying other documents, yes, but I see no reason to conclude that La

Harpe, Casañas, and St. Denis were all copying Joutel (or each other)—they seem

to all be separate and independent witnesses.

Another

possible explanation is that the various spellings of "Quiohuan" are

all based on an intermediate Indian language, one in which the original [≈kaiwa]

had become [≈kiowa]. Like the previous

explanation, this removes the statistical unlikelihood of numerous identical

mutations by positing only one mutation instead. Unfortunately, however, it's an appeal to

nonexistent evidence: no such intermediary form is attested in any Indian

language that could have been the source of the kio- spellings. Joutel explicitly

says he heard the name from a (Caddo-speaking) Kadohadacho chief, and it's hard

to believe any of the other authors got their versions via any language other

than Caddo or Wichita. But the name for

the Kiowa in the Caddo and Wichita languages is Káhiwaʔ and Káhiwaʔa,

respectively. Not **Kihowaʔ or whatever you might want for this explanation to work.

Another way

to wave away the anomaly, is to say that the "Quio-" spelling or the kio- pronunciation is just a French idiosyncrasy

that arises for some reason. This

explanation can be easily dismissed on both sides. For one, "Quiguaya" and

"Quihuugan" both look to be kio-

names, yet they both come from Spanish

documents. For another, the first time

that the Kiowa are unambiguously named (i.e. in their historically attested

location) in a French document, that document uses a kai- spelling: the document in question is by Perrin du Lac in

1802, the location is western South Dakota, and the spelling is

"Cayoavvas" (Mayhall 1971:23).

This proves that Frenchmen were entirely capable of accurately writing

[≈kaiwa] if they wanted to. The fact

that both they and the Spaniards only

wrote [≈kiowa] when referring to a tribe in/near eastern Texas, and never wrote it anywhere else... means

that the tribe in/near eastern Texas was not the Kiowa. The

Quiohuan were not the Kiowa.

I'm pretty

sure I am not being circular in my argument.

I didn't pre-select all of the kio-

names because they were kio- names and then say: Hey! Look!

They're all kio- names! The chronological and geographical separation

of the Quiohuan from the Kiowa is real. So

is the consistent way in which one group is called by kio- names, and the other by kai-

names. There is no overlap, and no

exception to the pattern, and it cannot be explained away as happenstance. The evidence points to the existence of two

different, unrelated Native American tribes: the Kiowa and the Quiohuan.

|

Locations associated with the Kiowa and Quiohuan. K1: Kiowa homeland (pre-1700). K2: Montana plains (1700-1775). K3: Black Hills (pre-1775). K4: Location of Cheyenne, who shared territory with the "Cayoavvas" according to Perrin du Lac (1802). K5: North Fork of the Platte River, location of the "Kiawas" according to William Clark (1804). K6: Arkansas River, location of Kiowa-Comanche truce (1806). Q1: Kadohadacho village visited by Joutel (1687). Q2: Hasinai villages visited by Casañas and St. Denis (1691-1717). Q3: Natchitoches village visited by St. Denis, also the location of the "Quiouahans" according to the anonymous Mémoire (1717-1718). Q4: Location of the "Quiohuan" reported by M. du Rivage (1719). C: New Mexico, where Spanish documents record the presence of "Caiguas" (1727 and after). P: Possible location of the "Pioya" or "Piwassa" encountered by La Vérendrye (1742).

|

I know of

only one putative counterexample to the pattern that the Kiowa are never unambiguously called

by a kio- name. I say

"putative" because in fact it is not actually a counterexample, as I

will explain:

In 1742, François

de La Vérendrye departed from the Mandan villages in North Dakota and headed

southwest, trying to find any Indian group who might direct him to the Pacific

Ocean. He never reached the Pacific, and

had to turn back after coming near to an unidentified mountain range which

people have since speculated may have been the Black Hills, the Bighorn

Mountains, or the Wind River Range. All

three possibilites would place La Vérendrye's itinerary in or near Kiowa territory.

La

Vérendrye's account mentions several Indian groups that his expedition

encountered, some of which may have been tribes, others bands within a single tribe. The tribes or bands are identified using

names that are descriptive but not very helpful: the Bow People, the Beautiful

Men, the Little Cherry People, etc.

However, one group is named phonetically rather than in translation: the

Pioya. It has been said that these "Pioya"

were the Kiowa, and that the name results from somebody miscopying an earlier

manuscript in which the name was spelled "Kioya".

Unfortunately,

this theory is rendered unlikely by the existence of a summary of La

Vérendrye's expedition written by Louis-Antoine de Bougainville in 1757. Bougainville apparently, somehow, had more

information on the Indian tribes encountered by the expedition than La

Vérendrye gives in his own account (perhaps he had an inside source), and he gives for each tribe their Cree or Ojibwe appellation in addition to the French.

This makes it easier for modern linguists to identify them.

As for the

Pioya, Bougainville calls them the "Piwassa" and says that this name

means "Grands-Parleur" or Great Talkers (Parks 2001). Unfortunately this still doesn't tell us who

the Pioya were, since apparently neither Pioya

nor Piwassa are recognizable words in

any Native American language. But if the two

versions of the name are at all related, then it means that "Pioya" is probably close to the original form—in other words, it is not a misprint for

"Kioya". Also of note: the

name "Kiowa" does not mean "Great Talkers"—supposedly, it

means "Elks".

That doesn't

prove that the Pioya were not the Kiowa, of course. But it does prove that at least the name

"Pioya" has nothing to do with the name "Kiowa". And that means that what I said before still stands: that

the Kiowa are never anywhere referred to using a kio- name.

So in

summary, I do not think that the Quiohuan were the same people as the

Kiowa. I do not know who the Quiohuan were—some tribe of eastern

Texas or southern Oklahoma or maybe western Louisiana or Arkansas... often

enemies of the Caddo, especially the Hasinai—but they were not the Kiowa. Maybe they were a small tribe who (like so many

in the 18th century) merged with others to form a new corporate tribal entity,

losing their previous identity in the process. Maybe the name "Quiohuan" is

synonymous with some other Native American group that usually goes by a

different name. Maybe they were all

killed...

... Or maybe

they were the Kiowa. Shit, I dunno.

( Postscript:

One group who I have not mentioned is the "Marhout" or "Manrhout",

a tribe who according to La Salle lived south of the Wichitas in 1682-3 (Wedel 1973;

Hickerson 1996). La Salle mentions the Manrhout alongside another tribe called the "Gatacka", a name that usually refers to

the Kiowa-Apaches (from Pawnee Katahkaaʾ),

and it is for this reason people often say that the Manrhout were the

Kiowas. The reason I haven't mentioned them before now

is because I see no good reason to think that the Manrhout were the Kiowas, or

anyone else in particular. The name

"Manrhout" is not attested anywhere else except in sources based on

La Salle. Furthermore, the word katahkaaʾ in Pawnee refers not only to

the Kiowa-Apaches but also to "any tribe west of the Pawnees" (Parks & Pratt

2008), so it's not as useful as some would have you think. )

Notes

1.

Joutel also mentions a "Quouan" tribe earlier in his

account. I don't know if that is related—I

haven't seen anyone else mention them when discussing the Kiowa or Quiohuan.

2. The

name "Les quiohohouans" appears in Voyage a la Louisiane, et sur le Continent de l'Amérique Septentrionale

by Baudry des Lozières (written 1794-8), evidently the last time any variant of

the name Quiohuan appears in a historical document. The name appears on a list of apparently all

the Indian tribes of Spanish Louisiana that B. de Lozières was aware of. Other than that, nothing is said about

them. Since the list also includes the

names of several other obscure tribes which were probably gone by 1794, I

assume that Lozières was copying numerous older sources, and that this is also

where he heard about the "Quiohohouans".

3. The

Mémoire seems a little odd to me

(maybe blame Google Translate). Sometimes

its "Rivière Rouge" seems to be referring to the Red River, sometimes

to the Arkansas River. The "Innatchas"

are the Natchez, the "Aouayeilles" are the Avoyel (a Natchezan

tribe), and the "Touacanna or Paniouassas" are the Tawakoni Wichitas. The "River of the Otouys" probably

refers to the Osotouy, a Quapaw group who lived near the confluence of the

Arkansas and Mississippi rivers, and not to the Otoes who lived way further

north.

4. I'm

only considering the modern, standard pronunciation of English

"Kiowa". English spelling is

such a trainwreck that any attempt to interpret the intended pronunciations of

historical English spellings would just muddy the data.

5. Not to go into the niceties of Spanish phonology in the main body text... Historically the phoneme /w/ in Native languages was often rendered <u>, <hu>, or <gu> by Spanish writers. Spanish itself has no such phoneme, so for monolingual speakers this would probably be more like [kaiɣua] or [kaixua], which are close enough. Meanwhile, modern

Spanish has apparently borrowed "Kiowa" from English in both spelling and pronunciation, at least going off of Spanish Wikipedia and this video.

Sources

(primary):

[anonymous],

Mémoire sur les Natchitoches [undated,

probably written shortly after 1718].

Published in: Pierre Margry (ed.), Découvertes

et Établissements des Français dans l'Ouest et dans le Sud de l'Amérique

Septentrionale, Vol 6:228.1886.

Louis-Narcisse

Baudry des Lozières, Voyage a la

Louisiane, et sur le Continent de l'Amérique Septentrionale, fait dans les

années 1794 à 1798. 1802.

Jean

Chevalier de Beaurain, Journal Historique

de l'Établissement des Français a la Louisiane. 1831. (Allegedly a rewrite of La Harpe, Relation du Voyage.)

Francisco

Casañas de Jesús María, Letter and Report

of Fray Francisco Casañas de Jesus Maria to the Viceroy of Mexico, Dated August

15, 1691 [1691]. Spanish text in:

John Swanton, Source Material on the

History and Ethnology of the Caddo Indians. 1942. English translation in: Descriptions of the Tejas or Asinai Indians, 1691-1722, tr. Mattie

Austin Hatcher. 1927.

Jean-Baptiste

Bénard de La Harpe, Relation du Voyage de

Bénard de La Harpe [1718-20]. French

text in: Pierre Margry ed., Découvertes

et Établissements des Français dans l'Ouest et dans le Sud de l'Amérique

Septentrionale, Vol 6:243. 1886.

English translation in: Account of

the Journey of Bénard de la Harpe: Discovery Made by Him of Several Nations

Situated in the West, tr. Ralph A. Smith. 1958.

François de

La Vérendrye, Journal of the Voyage Made

by Chevalier de la Verendrye, with One of His Brothers, in Search of the

Western Sea Addressed to the Marquis de Beauharnois [1742-3], tr. Anne H.

Blegen. 1925.

Henri

Joutel, The La Salle Expedition to Texas:

The Journal of Henri Joutel 1684-1687 [1684-7], tr. Johanna S. Warren, ed.

& commentary William C. Foster. 1998.

Louis

Juchereau de St. Denis, St. Denis's

Declaration Concerning Texas in 1717 [1717], tr. Charmion Clair Shelby. 1923.

Sources

(secondary):

David M.

Brugge, Some Plains Indians in the Church

Records of New Mexico. 1965.

William C.

Foster, Introduction and commentary in The

La Salle Expedition to Texas: The Journal of Henri Joutel 1684-1687. 1988.

Sally T.

Greiser, "Late Prehistoric Cultures on the Montana Plains", in Karl

H. Schlesier ed. Plains Indians: A.D.

500-1500: The Archaeological Past of Historic Groups. 1994.

James H.

Gunnerson & Dolores A. Gunnerson, "Apachean Culture: A Study in Unity

and Diversity", in Keith H. Basso & Morris E. Opler ed. Apachean Culture History and Ethnology. 1971.

Pekka

Hämäläinen, The Rise and Fall of Plains

Indian Horse Cultures. 2003.

Kenneth E.

Hendrickson, Jr., "Brazos River”, in the Handbook of Texas Online, published online: 2010.

Nancy P.

Hickerson, "Ethnogenesis in the South Plains: Jumano to Kiowa?", in

Johnathan D. Hill ed. History, Power, and

Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Americas, 1492-1992. 1996.

Elizabeth

A. H. John, Storms Brewed in Other Men's

Worlds: The Confrontation of Indians, Spanish, and French in the Southwest,

1540-1795. 1975.

—, An Earlier Chapter of Kiowa History. 1985.

Jerrold E.

Levy, "Kiowa". In Handbook

of North American Indians Vol 13(2). 2001.

Robert H.

Lowie, Alleged Kiowa-Crow Affinities. 1953.

Mildred P.

Mayhall, The Kiowas. 1971.

William C.

Meadows, New Data on Kiowa Protohistoric

Origins. 2016.

James

Mooney, Calendar History of the Kiowa

Indians. 1898.

John H.

Moore, Margot P. Liberty, A. Terry Straus, "Cheyenne". In Handbook of North American Indians Vol

13(2). 2001.

William W.

Newcomb, Jr., Historic Indians of Central

Texas. 1993.

Morris E.

Opler, "The Apachean Culture Pattern and Its Origins". In Handbook of North American Indians Vol

10. 1982.

Scott G.

Ortman, Winds from the North: Tewa

Origins and Historical Anthropology. 2012.

Scott G.

Ortman & Lynda D. McNeil, The Kiowa

Odyssey: historical relationships among Pueblo, Fremont, and Northwest Plains

peoples. 2017.

Douglas R.

Parks, "Enigmatic Groups". In Handbook of North American Indians Vol 13(2). 2001.

Douglas R.

Parks & Lula Nora Pratt, A Dictionary

of Skiri Pawnee. 2008.

Daniel J.

Prikryl, Fiction and Fact about the

Titskanwatits, or Tonkawa, of East Central Texas. 2001.

David

Leedom Shaul, A Prehistory of Western

North America. 2014.

Mildred

Mott Wedel, The Identity of La Salle's

Pana Slave. 1973.