So

a while back I was reading through some of the archives of the Siouan Mailing List, which is/was one of the best things on the internet, but has since

(apparently?) died off because I guess now people use Facebook or

something. But while it lasted it was

great, because it was like being a fly on the wall during conversations between

all of the big names in Americanist linguistics: people like Ives Goddard and Marianne

Mithun, as well as a few people who are no longer around: Wallace Chafe, Blair

Rudes, Robert Rankin. We shall not see

their like again.

But

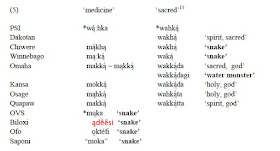

something caught my eye when I saw a post that included the following table,

showing the reflexes of two similar but distinct roots in the Siouan languages:

|

| (The same table was published in Oliverio & Rankin 2003. I've overwritten the Biloxi entry and replaced it with the orthography given in Kaufman 2011.) |

What

you see in these words is a conflation of the concepts "holy" and

"snake", with a little bit of "water monster" along the

lines of the Ojibwe Mishi Bizhiw. This conflation was an areal feature of the

Ohio Valley district where Proto-Siouan was once spoken, and it affected the

neighboring Algonquian languages as well (Siouan Mailing List 2013). The people who lived there apparently

worshipped snakes. Jean-Bernard Bossu

saw the Quapaw (originally from the Ohio River) worshipping snake idols in the

1600's. There might also be some

connection with Serpent Mound in Ohio.

But

what caught my eye was the entry for Ofo: o̢ktéfi. According to Oliverio and Rankin, the "dêêsi"

in ądêêsi and the "ktefi"

in o̢ktéfi is the root for "striped"

or "spotted"; "ą" and "o̢" are the original roots,

descended from Proto-Ohio-Valley-Siouan *mu̢ka. O̢ktéfi

thus has a perfectly ordinary etymology in Ofo.

Which

makes it curious how much the word resembles "uŋktéȟi" (variants: uŋȟčeǧi,

uŋkteȟila, etc.), the name of the legendary water monster in Lakota

mythology.

|

| Also apparently a "Rank A Elite Mark" in Final Fantasy XIV. Killing it rewards the player with up to 40 Allied Seals, 20 Centurio Seals, 30 Allagan tomestones of Poetics, and 10 Allagan Tomestones of Mendacity! |

This

can't just be down to Ofo and Lakota both being Siouan languages, descended

from a common parent. The similarity is

too close, and besides that, the proper cognate of o̢ktéfi in Lakota would be something like wakȟáŋ gléška—not anything like uŋktéȟi.¹ This word has to have been borrowed.

Furthermore, it must have been borrowed from

Ofo or Biloxi specifically, since the Lakota form begins with a nasalized vowel,

whereas the ancestral roots begin with *w and *m. Word-initial m and w are regularly

lost in Ofo and Biloxi, in a sound change peculiar to those two languages alone

(Larson:

80, Rankin et al. 2015:11,143).

Moreover, it was more likely borrowed from Ofo rather than Biloxi

(unless it was some other, unattested Mosopelean language). The value of the initial nasal vowel and of

the "kt" consonant sequence matches near-exactly between Lakota and

Ofo, while the Biloxi form doesn't match nearly as well.

And,

importantly, it looks like the Sioux borrowed the word directly from Ofo, not via an intermediary language, because I

can't find a word in any Siouan language that could have been an

intermediary. Ioway has Ischéxi for the Horned Water Panther,

which is clearly related, but that doesn't resemble either the Ofo or Dakotan

as much as they do each other (Goodtracks).

And I don't think Dakotan can have borrowed it via an Algonquian

language, since those don't have phonemic nasal vowels (and afaik wouldn't

allophonically nasalize a vowel in that position).

I

can't be the only person who's noticed this, although I've never seen anyone

discuss specific interactions between the Sioux and the Ofo. Within the Siouan family, the two are mostly

treated as pretty far-flung. But there

seems to have been contact and borrowing at least for this term: the question

is when and where? The similarity to the

Ofo and not the Biloxi form means it must have occurred after the Ofo and the

Biloxi separated from each other. Robert

Rankin dated the Ofo-Biloxi split to between 600 and 1100 A.D. (Rankin 1996,

Kaufman 2014:12).

|

| Source: Robert Rankin (2007) |

Furthermore,

it looks to me like it was borrowed after

Ofo underwent the distinctive s → f sound

change, which may have still been active in the 17th century (Siouan

Mailing List 2007). The Old Ofo

form *o̢ktesi would have been

borrowed into Dakotan as "uŋktesi".

The ȟ in uŋktéȟi may be the result of Dakotan-speakers attempting to

approximate the "f" of o̢ktéfi,

since that consonant is not ordinarily found in Siouan languages other than Ofo. A second possibility is that it was originally borrowed as

"uŋktesi" but was later modified to uŋktéȟi via Siouan sound-symbolic fricative gradation (s < š

< ȟ). The first option seems more

plausible to me.² This suggests a time

window of about 1000 to 1700 A.D.

* * *

Why

is that noteworthy? Because according to

the standard model, the Ofo-Biloxi and the Sioux were not particularly close to

each other at that time. The Sioux are

usually located in eastern Minnesota at the time of first contact, ca. the

1630's. According to

Guy Gibbon's summary of Dakotan prehistory, they had been within the Minnesota

area separate from the Central Siouans by 700 A.D. (Gibbon: 36). The Lakotas' subsequent expansion into the

Dakotas [the states] was largely an event of the 18th century.

|

| Variants of the name "Mosopelea" appearing in historical documents (Rankin 2007). |

The Mosopelea are said to

have first been met by white men when Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet explored

down the Mississippi River in 1673.

Marquette wrote in his journal of meeting a certain tribe somewhere

along the Mississippi north of the Akansa (Quapaw) and Michigamea

settlements. He doesn't give this tribe

a name, and provides no useful information in his journal at all other than

that they didn't speak Huron. But Marquette's

map from 1674 apparently calls them "Monsȣpelea" (<ȣ> is an old way of writing <ou>), and locates them

around western Tennessee:

Other maps, based on that

of Louis Jolliet⁴, place them either south of the Quapaw nearer to the Gulf of Mexico, as

on the following "Anonymous" map (Delanglez: 69):

|

| Does that say "Aganatchi" up there in the corner? As in "Akenatzy", as in the Occaneechi? What on earth are they doing on the Mississippi River? |

Or they split the

difference and place the Mosopelea in both locations, as on the

Thevenot-Liebaux map of 1681:

|

| "Monȣperea" in Mississippi and "Monsȣperia" in/near Tennessee. |

Carl

J. Weber has claimed that the Marquette and Anonymous map are both fakes (see

here and here), but I haven't yet seen him say the same of the

Thevenot-Liebaux. Even if all these maps are fake, though, the

existence of Mosopeleas on the east side of the lower Mississippi is supported

by the written accounts of Henri Tonti and Anastasius Douay. It's probably safe to say that Jolliet and

Marquette did indeed run into the Mosopelea in 1673, somewhere on the Mississippi River.

My

reading of the Marquette journal suggests to me that the more southerly

location is the correct one: the Quapaw told the French that the tribe they had

seen north of the Michigamea were a tribe whose permanent residence was south

of the Quapaw and who barred all access to the lower Mississippi River trade (Thwaites: 155). This is also close to where the historic Ofos

were located.

Franquelin

got his information for this map from La Salle (who got his information from the Shawnee).

What La Salle knew can be gleaned from a letter he wrote in 1681, in

which he lists a series of Indian tribes who had been ousted from the Ohio

Valley province by the ravages of the expanding Iroquois nation... one of these

conquered tribes he identifies as the "Mosopelea" (Hanna: 97). According to Charles Hanna, this conquest

occurred sometime between 1654 and 1672.

|

| Drainage area of the Miami, Scioto, and Muskingum river systems. (Based on maps by Wikipedia user Kmusser) |

Furthermore,

the Shawnee called the Ohio River the Msipelewa,

and the Illini called it the Pileewa

Siipiiwi—both evidently referencing the (Moso)pelea (McCafferty: 49, Voegelin). These names have been analyzed as "Big

Turkey" or "Turkey River"—as indeed they may be—but I think a

connection with the Mosopelea is extremely likely. Folk etymology may also be at play here, as

it later was for the name "Ofo".⁵

Thus,

the original home of the Ofo/Mosopelea—or at least, their home before 1673 when

they lived in Mississippi—was on the north side of the Ohio river, possibly in

the modern state of Ohio.

One

might think that the Illini and Shawnee calling the Ohio river the "Turkey

River" might have nothing to do with the Mosopelea of Mississippi—that

it's just a chance resemblance—but for the fact that linguistically Ofo is

within the eastern division of the

Siouan languages. Its closest documented

relatives are Tutelo (from Virginia) and Biloxi. So where were the Biloxi?

As

far as I know the first time the Biloxi are reported under that name is when Pierre LeMoyne d'Iberville encountered a

group of "Bylocchy" in southern Mississippi in 1699.⁶ And for a long time, that was all there was to

say. But more recently researchers have

been finding early traces of the Biloxi farther to the east. In a recent article, David Kaufman, an expert

on the Biloxi language, looked at a series of person and place names from old English

and Spanish documents, and found evidence that the Biloxi ("Tomahitans")

were in Kentucky and Tennessee, in the Cumberland Plateau and Mountains district—in

1540, 1566-8, 1585, and 1673 (Kaufman 2018).

Their subsequent migration to Louisiana was presumably triggered by the

same one-two-punch of Iroquoian conquerors and Carolinan slavehunters that made

everyone else vacate the Woodlands interior in the late 1600's.

So,

following Hanna and Kaufman, one can give a maximal interpretation for Ofo and

Biloxi territory circa the early 1600's like so:

|

| Emphasis on "maximal": it's unlikely their territories were this big. |

Not

everyone agrees with this hypothesis. A

common alternate position is that the Cumberlands belonged to the Cherokee

and/or the Yuchi—and for all I know maybe all three tribes lived in that

area. Many people also say that the

Tomahitans were the Cherokee. And to be fair, I don't accept all of

Kaufman's proposal's either.⁷ So I don't

know for sure what's true... but until I look into this matter further, I'm

going to proceed as if Kaufman is correct (I'm biased in favor of linguistics-based

theories anyway). In any

case, one can assume that the ancestral Ofo and Biloxi had been living within

the same general area since the division of the Proto-Ofo-Biloxi language ca.

600-1100 A.D. Both languages are also

closely related to Tutelo, formerly spoken in Virginia. So Cumberland or not, the early Biloxi were

certainly not too far from that

general region.

* * *

If

I'm right about uŋktéȟi being loaned

from o̢ktéfi, then the Sioux must have been in close contact with the

Ofo—either before the latter moved from the mid-reaches of the Ohio River, or

after they had migrated to Mississippi.

Since the Sioux were established in Minnesota by 700 A.D. according to

the archaeological evidence, then if this contact was pre-Ofo migration it

would imply that the Sioux were still ranging southeastward into the Ohio

valley.

The

sound change in Ofo that shifted /s/ to /f/ can be dated to within a certain

time window. The name for the Ofos in

the language of the Tunicas (then in Arkansas) was Úšpi, borrowed from a form of (M)osope(lea) that was caught in

between the two Ofo sound changes I mentioned above. So at least some Ofos were still speaking

their language with an "s" by the time they moved into the lower

Mississippi Valley and came into contact with Tunicas—after the exodus of

1654~1672.⁸ And by 1699, at least some

were speaking with effs, as the tribe is recorded as "Opocoula" in

the journal of Pierre LeMoyne d'Iberville.

If

Dakotan borrowed the word uŋktéȟi

directly from Ofo o̢ktéfi, then it

had to have been after 1672, along nearly the entire length of the mighty Mississip. That would make for a curious example of

cultural diffusion. On purely phonetic

grounds I think that this is more likely, which raises my eyebrows as to how

and why the Sioux were importing mythic tropes from Mississippi. On the other hand, if it was borrowed from

Old Ofo o̢ktési (with the ȟ produced by sound symbolic fricative

gradation), then it is still curious to note as a relic of long-gone neighborly

relations between two far-flung members of the Siouan family.

* * *

There's

an old Sioux legend that speaks of the uŋktéȟi

("Umketehi") guiding the Sioux into Minnesota from their ancestral

home in the east (Gibbon: 18); that almost sounds like it could be related to this, somehow.

The same story, as it descended to the

Ponca, spoke of the Poncas moving west across Nebraska and encountering a

monster called the "Wak-kon-da-gee" (cf. Omaha wakką́dagi) (Mason: 161).

This Ponca version of the tale was later reinterpreted (by the whites or

the Poncas, I do not know) as being a first-hand account of an encounter with a

live mammoth. I also know that it's the

opinion of some that the Lakota story of uŋktéȟi

is a memory of North American mastodons and mammoths, carefully passed down to

the descendants of those who once hunted them during the Ice Age.

It's

entirely possible that the uŋktéȟi ~ wakką́dagi ~ ischéxi ~ o̢ktéfi ~ mishibizhiw is a representation of a

mammoth, but not because it's a story surviving from the Pleistocene—but

because it's an interpretation of mammoth fossils. Siberian mythology (from which we get the

word "mammoth") is rather explicit on this point, from what I hear. And then there's the theory that the Greek

cyclops is an interpretation of extinct elephant skulls, which look like they

have a single eyesocket in their forehead.

French and English people used to wonder whether the old

"elephant" bones they found in America meant that there was a species

that lived further into the interior. I

can't imagine just walking along and coming across the skull of a mammoth, but

I guess it used to be easier to find these sorts of things back when the whole planet

hadn't yet been scoured by paleontologists and ivory smugglers.

|

| Elephant skull. Note the cyclopean fossa on the forehead. |

But

people don't need fossils to tell stories about monsters, and I suspect the uŋktéȟi is... probably... not a mammoth. The beast has all the hallmarks of its

eastern origin as the Horned Panther—including an association with bodies of

water—not of a hulking hairy herd animal.

If the Plains folk ever made it one, that's probaly just because there were more

buffalo and fewer lakes there than in the Woodlands. Siouan myth in general is something of a

mixture of eastern and western memeplexes, e.g. the story of Creation is

sometimes that of the underground Emergence (a Plains trope), sometimes that of

the descent of Sky Woman (an Eastern trope, most well-known in the Iroquois edition). And of course, the fact that o̢ktéfi and its Chiwere-Winnebago cognates

came to mean "snake" shows that not all interpretations of the

creature have been mammalian.

That aside, the existence of the Lakota uŋktéȟi

myth (and especially the word "uŋktéȟi"

itself) is evidence of something pertaining to early North American history, though

I'm not really equipped to say exactly what.

But it appears that the name of the Water Panther was borrowed from Ofo

into Dakotan... somewhere, somewhen, possibly after 1672 along the Mississippi

River corridor. It was then borrowed

from Dakotan into Ioway, despite the Ioways being located in between the Ofos and the Sioux.

Strange indeed. But I don't have

much to say beyond that. If you want to

know more about the legend of the Water Panther, I recommend reading Mii Dash Geget's essay.

Notes

1 – Wakȟáŋ gléška is what was suggested to

me, but that uses the modern Lakota word which derives from the other Proto-Siouan

root, *wahką́. I don't know historical Siouan phonology but

I'm guessing a true cognate, if it existed, would be maybe "máŋkȟa

gléška". The point remains.

2 – Siouan

sound symbolism seems to usually operate in words whose meanings are...

subjective? Experiential? Impressionistic? Ideophonic?

I don't know how to describe it, but some examples of words that have

sound symbolism in their Siouan translations are "jingle",

"rattle", "slick", "smooth", "black",

"dirty", "pink", "red", "firm", and "humpbacked". "Snake" doesn't really fit in here, although I could certainly be wrong.

3 – Michael

McCafferty doubts the identity of the Mosopelea and the Ofo, and apparently

thinks the former were a division of the Shawnee. Pace eī,

I think the linguistic connection and the geographical proximity of the

latter-day Mosopelea to the historic Ofo are simply too compelling to dismiss.

4 – The

original Louis Jolliet map—assuming that it is the "Map of the

Griffons" as Campeau supposes (McCafferty 2008:182)—doesn't appear to include the

Mosopeleas.

5 – The

Choctaws' name for the Ofos, Ofogoula

(literally "Ofo people") was reinterpreted as meaning "Dog

People", from ofi the Choctaw

word for "dog".

6 – In an

early ethnography of the Biloxi, James Owen Dorsey wrote that "in 1669,

according to Drake, the Biloxi had their village on Biloxi Bay, Mississippi,

near the Gulf of Mexico" (Dorsey: 268).

However, he gives no further citation for this information, and I can't

figure out who "Drake" even is (Wikipedia lists no other famous Drake

who was active in 1669; Sir Francis had been dead for 73 years).

7 – E.g.

Kaufman cautiously proposes that the "Chawanocks" of North Carolina

may have a Biloxi connection because it "contains the ending –ks, as in the Biloxi autonym

Tanêks". I can't speak for whether –ks is a Siouan gentilic suffix or not,

but the ending of "Chawanocks" looks more like a pleonastic plural made

of Algonquian –ak and English –s anyway.

8 –

According to Mary Haas, Tunica has /f/ as a phoneme occurring in loanwords,

though she doesn't specify if those are early loans from e.g. Choctaw or late

loans from e.g. English and French. Also

according to Haas, Biloxi has /f/ as an allophone of /x/, but not of /s/. Ofo is also not totally bereft of the

consonant /s/, it being the Ofo reflex of Proto-Ohio-Valley-Siouan *x. These facts when put together, I think, support

the hypothesis that Tunica Úšpi was

borrowed from Old Ofo *Osope rather

than from *Ofope, or even Ofo(pe) being a borrowing from Úšpi.

Sources

Jean

Delanglez, "The Jolliet Lost Map of the Mississippi". In Mid-America:

An Historical Review, New Series Vol. 17 no. 2 (1946).

James Owen

Dorsey, "Address of Vice President, James Owen Dorsey: The Biloxi Indians

of Louisiana". In Proceedings of The American Association for

the Advancement of Science for the Forty-Second Meeting (1894).

Guy Gibbon, The Sioux: The Dakota and Lakota Nations

(2002).

Jimm

Goodtracks, Ioway-Otoe-Missouria

Dictionary (1992, rev. 2007).

Mary R.

Haas, "A Grammatical Sketch of Tunica." In Linguistic

Structures of North America, ed. Harry Hoijer (1946).

— "The

Last Words of Biloxi." In International Journal of American

Linguistics Vol. 34 no. 2 (1968).

Charles A.

Hanna, The Wilderness Trail Vol. 2

(1911).

David V.

Kaufman, Tanêks-Tąyosą Kadakathi:

Biloxi-English Dictionary with English-Biloxi Index (2011).

— The Lower Mississippi Valley as a Language

Area. PhD diss. (2014).

—

"Biloxi Origins". In Native South Vol. 11 (2018).

Rory Larson,

"Regular sound shifts in the history of Siouan." In Advances

in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics, ed. Catherine Rudin &

Bryan J. Gordon (2016).

Ronald J.

Mason, Inconstant Companions: Archaeology

and North American Indian Oral Traditions (2006).

Michael

McCafferty, Native American Place-Names

of Indiana (2008).

Giulia R.

Oliverio & Robert L. Rankin, "On the Sub-grouping of the Virginia

Siouan Languages" (2003).

Robert L.

Rankin, "On Siouan Chronology" (1996).

—

"Siouan Tribes of the Ohio Valley: 'Where did all those Indians come

from?'" (2007).

Robert L.

Rankin et al., Comparative Siouan

Dictionary (2015).

Siouan

Mailing List Archive for March 2007, "Autonym of

Mosopeleas-Ouesperies-Ofos".

Siouan

Mailing List Archive for November 2013, "The two meanings of wakan".

Reuben Gold

Thwaites ed., The Jesuit Relations and

Allied Documents Vol. LIX (1900).

Erminie W.

Voegelin, "Indians of Indiana".

In Proceedings of the Indiana

Academy of Science Vol. 50 (1940).